Heung | 흥 Coalition

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

︎ Instagram

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

Toward a New Afro-Asian Solidarity: Revisiting Cold War Politics in DA 5 BLOODS, WATCHMEN, and LOVECRAFT COUNTRY

November 17, 2021

By: Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi and Rachel Lim

Collage by Grayson Lee

HBO’s supernatural horror series Lovecraft Country (2020) follows Atticus, a Black veteran recently returned from the Korean War, as he confronts the terrors of mid-century American racism, both mundane and paranormal. In Episode 3, after his childhood friend Leti purchases a rundown mansion in North Side Chicago, they are subjected to racial intimidation by their new white neighbors, who tie bricks to their car horns and place a burning cross on their front lawn. But Leti’s new home is also haunted, quite literally, by the historical remnants of racism. The previous owner, a white doctor, conducted horrific experiments on his Black victims, whose names— Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy — recall the names of enslaved Black women subjected to medical torture. Their spirits still roam the hallways, appearing in mirrors, pulling sheets off beds, and slamming doors shut. In one harrowing basement scene, a ghost turns up the boiler, heating the house to unbearable levels and bringing Atticus and Leti to the basement to investigate.

“Excessive heat and noise,” says Atticus, wiping his brow. “Same tactics we used in Korea.”

In Lovecraft Country, in addition to two other major cultural productions — Spike Lee’s film Da 5 Bloods (2020) and the television remake of the comic book Watchmen (2019) — Black Americans struggle with the spectral legacy of anti-Black racism as well as the ghosts of US military intervention in Asia. The release of these cultural productions has been timely: this past year, Black Lives Matter protests have erupted across the country, calling attention to the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Daniel Prude, and many other Black individuals at the hands of the police. Since the first Black Lives Matter protests in 2013, there has been a wave of films, such as Selma (2013), Hidden Figures (2016) and the more recent One Night in Miami (2021), that situate the contemporary Movement for Black Lives within the United States’ much longer history of structural racism, with a particular focus on the Cold War period. But Da 5 Bloods, Watchmen, and Lovecraft Country are unique in that they center the role that US imperialism — signified by the Korean and Vietnam Wars — had on shaping Black subjectivity and Black politics, both during the Cold War period and today. In addition, all three cultural productions move beyond the Black-white binary to center the fraught relationships between Black and Asian communities. As scholars of the Cold War and its afterlives — more specifically, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and their postwar diasporas — we are interested in unpacking what these three immensely popular cultural productions tell us about how Cold War Afro-Asian relations are re-membered and re-imagined in the contemporary moment, as well as what models they can offer us in terms of Afro-Asian coalition-building in the present.

The Cold War moment was a defining period of Black subject formation. On the domestic front, African Americans fought for civil rights: the right to eat at desegregated lunch counters, the right to vote free of intimidation, the right to live in multiracial neighborhoods, and the right to work at a well-paying job— in sum, the right to aspire towards the American Dream. This was the era of Brown v. Board of Education, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and the March on Washington. On the international front, Black men played a key role in America’s imperial ventures. The Korean War marked the first time that the US army was desegregated. The Vietnam War, which followed soon after, highlighted the bitter ironies of integrating the military while the domestic neighborhoods remained violently segregated. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. powerfully noted in his famous “Beyond Vietnam” speech, delivered on April 4, 1967:

“[We watch] Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. So we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago.”

During the Cold War period, Black leaders and activists debated the best way to guarantee Black freedom. The Civil Rights Movement emphasized the domestic context, privileging non-violent forms of protest to fight for civil rights and inclusion. These activists ultimately believed that the United States could overcome its fraught history of slavery and racial capitalism in order to guarantee freedom and liberty for all, regardless of race. The Black radical tradition, epitomized by the Black Panther Party and Black Maoists, took a more transnational approach, understanding Black America as an internal colony of the United States that should build solidarities with other colonized subjects across the Third World, in a mutual decolonial struggle against imperialism and racial capitalism. The Black Panthers in particular promoted a politics of intercommunalism, which sought to transcend nation-state borders in order to articulate solidarities between different colonized communities suffering from the violence of US imperialism. They articulated Afro-Asian solidarity with spaces such as China, Korea, and Palestine.

At the same time, Black feminists such as Angela Davis, June Jordan, and the Combahee River Collective emphasized a need for an analysis through and across race, gender, and sexuality, to critique the heteronormativity and hypermasculinity pervasive in the majority of Black activist spaces as well as the white supremacist cultures they sought to counteract. In the words of the Combahee River Collective, “[T]he liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy.” Drawing from the Black feminist tradition, we unpack how Da 5 Bloods, Watchmen, and Lovecraft Country represents Cold War relations between Black and Asian subjects not only as a question of racial difference or decolonial alliance, but as kinships that must be understood across transnational matrices of gender and sexuality. We ultimately contend that genuine Afro-Asian solidarity must be grounded in queer, feminist, and anti-imperialist politics, which provide more capacious possibilities for coalition-building in the present moment.

***

Spike Lee’s film Da 5 Bloods (2020) follows the journey of a band of four African American Vietnam War veterans — the eponymous “Bloods” — who return to Vietnam in the contemporary moment in order to find the remains of their fallen squad leader as well as the gold fortune he helped them to hide. The film juxtaposes activism from the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement with visual and audio clips of Black activism during the Vietnam War, including quotes and images of Malcom X, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Muhammad Ali. In its treatment of Black veterans and their war experiences, the film is an important corrective to Vietnam War films such as Green Berets (1968), Apocalypse Now (1979), and Full Metal Jacket (1987) that centered the white GI perspective. At the same time, Da 5 Bloods reproduces the visual and narrative tropes of this filmic tradition that overwrite, and in effect erase, both communist and anti-communist Vietnamese subjects. As Viet Thanh Nguyen writes in his NYT review of the film: “In putting Black subjectivity at the center, Lee also continues to put American subjectivity at the center. If one can’t disentangle Black subjectivity from dominant American (white) subjectivity, it’s impossible to apply a genuine anti-imperialist critique.”

In other words, by narrowing the scope of Black activism to the domestic field of white-Black relations, Da 5 Bloods misses the opportunity to tap into the anti-imperialist politics of the Black radical tradition. Furthermore, by centering the Black male GI experience, Da 5 Bloods also overlooks Black feminist politics, which offers an astute critique of the toxic masculinity underwriting American imperial war-making, both during the Cold War and today. Indeed, we see a missed opportunity in the film’s treatment of Tien, a former lover of Otis (played by Clarke Peters) and their half-Black, half-Vietnamese daughter Michon. Although we were excited to see the film feature Black-Vietnamese model and actress Sandy Huong Pham, herself the daughter of a South Vietnamese mother and an African American GI father, for the most part the film fails the promise of Afro-Asian solidarity, insofar as it reproduces common stereotypes about Asian women. Tien, who the Bloods need in order to smuggle out the gold, recalls older iterations of the dragon lady, a mysterious figure who uses deceit and cunning to get her way. As we learn that other Vietnamese rejected Tien and called Michon racial slurs, we are reminded of the trope of the “tragic mulatta” — a beautiful, mixed-race woman who fails to find belonging in either her Vietnamese or Black heritage.

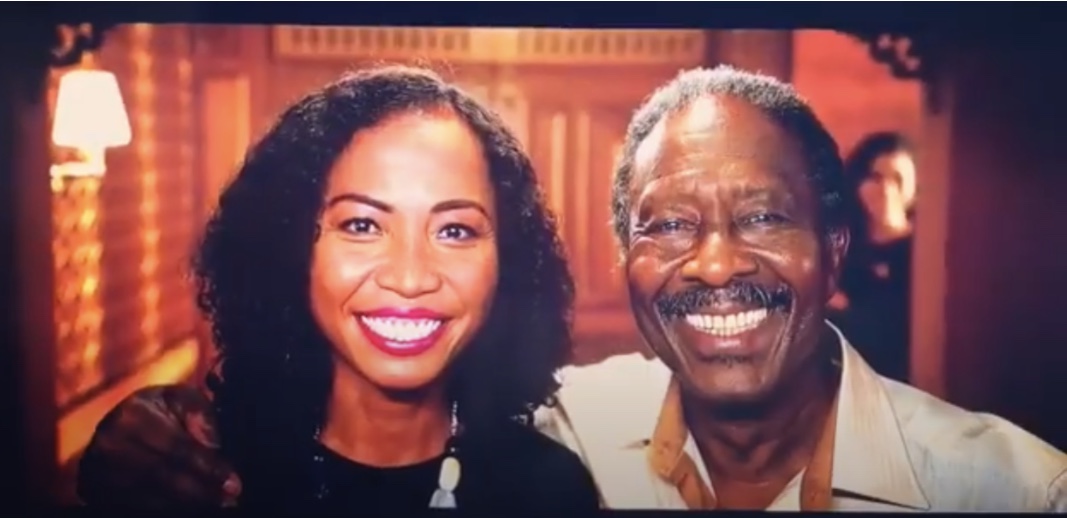

In one of the film’s final scenes, Otis is finally introduced to his daughter Michon. They embrace warmly; Michon says, “I miss you. And I love you so.” Otis responds, “And I love you.” This scene of reconciliation is particularly notable because, more often than not, Da 5 Bloods focuses on the incommensurabilities between the Black veterans and the people of Vietnam. In fact, the film portrays a litany of hostile encounters with Vietnamese men — gangsters, merchants, and hired mercenaries. Additionally, the very reason the Bloods were in Vietnam in the first place was to retrieve buried gold, which had been a payment to Indigenous Lahu soldiers allied with the US military — a claim that is framed as “reparations:” “We repossessed this gold for every single Black boot who never made it home, every brother and sister stolen from Mother Africa,” says the Bloods’ fallen leader Norman (played by Chadwick Boseman). In this framework, “reparations” is presented as a zero-sum game that occured at the expense of an already marginalized group in Southeast Asia.

Michon’s immediate acceptance of her father, who had been unaware of her existence, is another kind of reparative act that heals the wounds of the broken family and allows Michon to reconnect with her Black identity. The final shot of Michon and Otis presents them shoulder to shoulder, grinning straight into the camera in a manner reminiscent of a family portrait. But Michon’s mother Tien is not included; instead, her spectral image appears unfocused and blurry in the background, like a forgotten spirit. That is, the film suggests that the restoration of Michon’s connection to her Black father cannot co-exist on equal terms with her relationship with her Vietnamese mother. This fantasy of genealogical plenitude depends on a patriarchal definition of family in terms of biological reproduction rather than an ongoing ethics of care. By using the family snapshot to exclude Tien, Da 5 Bloods ultimately concludes by literally centering Black men against the backdrop of Vietnamese women. It forecloses, in sum, a more capacious feminist, anti-imperialist Afro-Asian politics.

Figure 1: Michon and Otis in Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods (2020)

***

Watchmen, HBO’s wildly successful 2019 mini-series, provides a much-welcome corrective to the hypermasculinity of Da 5 Bloods. Starring Regina King as Angela Abar and Hong Chau as Lady Trieu, the show reworks Afro-Asian relations during the Vietnam War and its afterlives by centering the relationship between these two women. Based on the celebrated graphic novel by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, in which Doctor Manhattan secures an American victory in Vietnam and Vietnam becomes the 51st state of the US, HBO’s 2019 remake asks: what if Doctor Manhattan took on the body of a Black man? What if he fell in love with a Black woman, who tragically lost both her parents to anti-imperial Vietnamese resistance fighters during the US war in Vietnam? Significantly, Watchmen emphasizes that not only Black men’s but also Black women’s subjectivity was profoundly shaped by America’s War in Vietnam, answering Vanita Reddy and Anantha Sudhakar’s 2018 call to consider “Feminist and Queer Afro-Asian Formations” that have been “marginalized, rendered illegible, or simply elided” by “a limited model of cross-racial brotherhood.”

At first blush, Watchmen improves on some of Da 5 Bloods’ shortcomings regarding the representation of its Vietnamese characters, given that it devotes key scenes in the season’s finale to fleshing out the backstory of Lady Trieu, named after Bà Triệu, the legendary third-century nationalist hero who resisted the Chinese occupation of Vietnam. In the opening scenes of Episode 9, we learn that Bian — Lady Trieu’s adult mother, not her reincarnated daughter — worked in the lab of Adrian Veidt, the mad scientist who had dropped a colossal alien squid on New York City in 1985, killing 3 million people in an attempt to prevent nuclear warfare and thus save the world. Bian sneaks into Adrian’s office and inseminates herself with Adrian’s semen, revealing that Lady Trieu is indeed Adrian’s daughter: equally brilliant, and equally aspirational. At age 20, she appears at the doorstep of Adrian’s hideout in Antarctica and reveals her master plan to create a quantum centrifuge to kill Doctor Manhattan, harness his powers, and “do all the things he should have done” instead of colonize Vietnam for the US: clean the air, make all nuclear weapons disappear, and render the Earth a better place. Although her goals are commendable, the means by which she intends to accomplish them — unavoidable sacrifice and unilateral power — are arguably no better than those of Adrian and Doctor Manhattan, and for this she is ultimately vilified as the show’s main antagonist.

Watchmen furthermore precludes the anti-imperialist possibilities imagined by Lady Trieu by rendering her the interpersonal enemy of the show’s protagonist and Doctor Manhattan’s lover, Angela Akbar. In doing so, it collapses the possibility of global Afro-Asian solidarity and sisterhood — routed through the Black queerness of Angela’s grandfather, Will Reeves — back into a domestic drama of white supremacy and anti-Blackness in the US. Black experiences of white terrorism, such as the infamous Tulsa Massacre of 1921 that open the show, ultimately convince Angela Akbar and her grandfather that they should fight the racist police state from within — that is, as antiracist cops — in effect blunting a more expansive critique of the links between US domestic policing of its minoritized subjects at home and US imperial policing of colonized subjects abroad, particularly during the Cold War period of Third World decolonization.

Figure 2: Lady Trieu and Angela in HBO’s Watchmen (2019)

In the end, Angela Akbar chooses the heteronormative love of Doctor Manhattan over Afro-Asian coalition with Lady Trieu, whom Aaron Bady in his LARB review of the mini-series describes as a “would-be avenger of colonial-violence-from-the-heavens.” Bady elaborates:

What’s strange about the show we actually got, in other words — the thing that makes it disappointing — is that it came so close. Two granddaughters are artificially made to recall the holocaust of their fore-parents: Bian’s artificially implanted memory evokes My Lai and other American massacres of Vietnamese people (“I was in a village, men came and burned it, and then made us walk. I was walking for so long, mom, my feet still hurt”) yet it’s so precisely what Angela’s grandparents might recall of Tulsa in 1921 that the coincidence can’t just be a coincidence. Yet instead of pressing this analogy into the space of solidarity, only one of these horrific experiences is shown to us in vivid, gruesome detail. The Vietnamese holocaust is always secondhand, overheard, the “murderer” scrawled across a mural of Dr. Manhattan. And because we do not see the terror of his victims, nor are we with them when they die, the parallels remain latent. Instead of reminding us that The Bomb really was dropped on Asian cities — and that every nightmare of what could happen if the Cold War exploded is patterned after massacres that really did happen across the world for the two centuries prior — the show retreats into making New York City the only civilian population whose experience of terrorism is given depth and psychological nuance.

Indeed, it is because Watchmen recenters American subjects — both Black and white — at the expense of elaborating the ways that Vietnamese subjects too suffered at the hands of the racist US state, that parallels between white supremacist violence against Black subjects in Tulsa and military imperialist violence against Vietnamese subjects in My Lai are elided. Ultimately, feminist, anti-imperialist Afro-Asian relations must move beyond a politics of representation — the celebration of Black and Vietnamese American women starring in such a major production — in order to more effectively address the necessarily transnational dimensions of Afro-Asian solidarity.

“Ultimately, feminist, anti-imperialist Afro-Asian relations must move beyond a politics of representation — the celebration of Black and Vietnamese American women starring in such a major production — in order to more effectively address the necessarily transnational dimensions of Afro-Asian solidarity.“

***

Lovecraft Country (2020), set in the 1950s, directs our attention to earlier moments of Black politics and subject formation. Like Watchmen, it highlights the Tulsa Massacre as a defining moment of white terrorism; though rather than beginning with Tulsa, Lovecraft Country takes the audience further back to the space-time of the slave plantation, highlighting the specific gendered violence suffered by enslaved Black women raped by white slavemasters. Like Da 5 Bloods and Watchmen, Lovecraft Country grapples with Black subjectivity during the Cold War’s “hot wars” in Asia, though this time the Vietnam War is replaced by the Korean War, which preceded the former by a decade and a half. Like Da 5 Bloods, Lovecraft Country centers a Black male veteran protagonist, Atticus “Tic” Black (played by Jonathan Majors). Unlike in Da 5 Bloods, however, Tic’s story is eclipsed by the strong Black queer and/or female characters that surround him: his queer father Montrose, his aunt Hippolayta, his cousin Diana, his lover Leti, and her queer sister Ruby. Indeed, unlike Da 5 Bloods and Watchmen, Lovecraft Country was written and directed by Black women — Misha Green and Victoria Mahoney — whose outlook profoundly shaped the show’s representation of not only Black subjectivity, but also Afro-Asian relations as routed through Black queer feminist interventions.

Throughout the first half of the show, Tic is haunted by memories of the Korean War, which manifest as the guilt and fear he shows whenever he thinks about his relationship with Ji-ah (played by Jamie Chung) while in Korea. At first, Ji-ah, as the show’s main Cold War Asian woman, seems to uphold a similar function as Lady Trieu in Watchmen. In Episode 6: “Meet me in Daegu,” Lovecraft Country shifts to the space of Korea to explain Ji-ah’s back story: she is a kumiho, the nine-tailed fox of East Asian lore who shapeshifts into a woman in order to seduce male victims and consume their flesh. Lovecraft Country gives its own twist to this East Asian legend, making the kumiho a spirit that possesses Ji-ah until she feeds on the souls of one hundred men. While Ji-ah spends her days tending to mens’ wounds as a nurse, at night she preys on their desires. Embodying both the “nurse” as well as “femme fatale” archetypes common to media productions about the Korean War, she lures them to a candle-ringed room, where she seduces them and, with Cthulhu-like tentacles, absorbs their memories and explodes them into a shower of blood.

Ji-ah first crosses paths with Tic when the US military suspects that there is a Communist spy among the Korean nurses. Tic is one of the soldiers who brutally participates in the murder of two innocent nurses and the torture of Young-ja, a Communist agent and Ji-ah’s best friend. When Ji-ah encounters Tic again, wounded in the hospital, she is filled with a desire for revenge and decides that he will be her one-hundredth and final victim. In a somewhat predictable fashion, Ji-ah and Tic bond over their mutual appreciation of Hollywood films and Western literature and fall in love. But when Ji-ah loses control of her kumiho powers with Tic, foreseeing his impending death and revealing her supernatural abilities, Tic is terrified and flees. Korea in Lovecraft Country, like Vietnam in Da 5 Bloods and Watchmen, risks becoming a mere backdrop on which to write the Black protagonists’ stories. And “Meet Me in Daegu” teeters dangerously on this line. The show is at its weakest when it centers Tic’s guilt for the violence he committed against innocent Korean civilians and uses Ji-ah’s love and forgiveness to absolve him of what are in fact heinous war crimes. (We might recall that more than half of the 5 million casualties of the Korean War were Korean civilians, constituting about 10 percent of Korea’s prewar population). As a Korean American viewer, the familiarity of the English-inflected Korean accents of Lovecraft Country’s Korean American cast was a continuous reminder that in the show, Korea was primarily positioned as a stage upon which a set of questions about US race relations were addressed.

Figure 3: Ji-ah and Tic in HBO’s Lovecraft Country (2020)

However, in its final two episodes, Lovecraft Country circumvents this foreclosure of Afro-Asian solidarity via the surprising narrative arc of Ji-ah. In the show’s penultimate episode, Ji-ah shows up at Leti’s house in Chicago in search of Tic, the last remaining human whom she had loved as a kumiho. Tic — arguably scared and emasculated by his last sexual encounter with Ji-ah, as well as worried that Ji-ah might disrupt his new romantic relationship with Leti — initially misreads Ji-ah’s desire to reconnect as a plea for heterosexual love and forcefully drives her out of the house. Later, he reaches out to Ji-ah and apologizes, affirming that the love that he kindled with Ji-ah in Korea was real and that it persists, albeit now within the valence of familial, platonic love. Ji-ah, unburdened by human distinctions between romantic, familial, and platonic love, accepts Tic’s apology, and tentatively inserts herself into Tic’s extended family, which includes not only his blood relatives but also Leti, pregnant with Tic’s son, and her queer sister Ruby.

In the final climactic scene of episode ten, Ji-ah sacrifices herself to help Tic — a sacrifice that, for those familiar with American orientalist narratives of the abandoned Asian lover, from Madame Butterfly (1932) to Miss Saigon (1989), is altogether expected. What is unexpected, though, is that Ji-ah does not die. Instead, in a stunning reversal, it is the American male protagonist, Tic, rather than than the scorned Asian lover, Ji-ah, who ultimately sacrifices his life for the “greater good” — understood in Lovecraft Country as the cessation of white Americans’ monopoly over magic, rather than the preservation of white Americans’ nuclear family structure. But by demonstrating her willingness to sacrifice her body to the darkness out of love for Tic and his family, even though she does not die, Ji-ah exemplifies a queer Afro-Asian love that is irreducible to heterosexual desire. And it is precisely this queer Afro-Asian love that exceeds and ultimately defeats the white supremacist patriarchal order of the Sons of Adam (which, in typical white feminist fashion, Christina Braithwhite had sought to circumvent by literally sacrificing a Black male subject in order to gain access into, rather than tear down, the white male patriarchal order that had excluded her).

Ji-ah, like the rest of Tic’s family, is pained by Tic’s death, but not consumed by it. In other words, the show ends with an opening — a gesture towards a queer, feminist Afro-Asian futurity. As Ji-ah walks somberly with the rest of Tic’s family with the fallen Tic in their arms, the show suggests that she will stay with Leti to help raise their baby, creating a queer, Afro-Asian family formation. This reading of the show’s ending and possible epilogue is supported, perhaps even foreshadowed, by two previous scenes of queer family formation. In an heart-warming scene from earlier in episode ten, Ji-ah joins Tic, Montrose, Hippolyta, Dee, Leti, and Ruby in singing the Chords' version of "Sh-Boom" as they drive together to Ardham, cementing her role as part of the family despite her non-Black Korean status. In an earlier scene, Tic’s mother Dora explains to Tic why and how she loved both his father Montrose and his uncle/possible biological father George, and why her refusal to choose between the two brothers made Tic stronger, since he could then inherit the qualities of all three adults. In making the case for queer family formations that exceed the heteronormative nuclear family, Dora sets a precedent for Ji-ah’s future role in parenting Tic’s child: a queer transnational kinship relation that could undermine American tendencies — including Black American tendencies — to read “Asia” as forever foreign and suspect.

At the same time, however, Ji-ah’s assimilation into the American family — and, by extension, the US body politic — reminds us that Lovecraft Country is ultimately an American story, in which the decolonial struggles of the Korean people are ultimately collapsed back into the framework of US race relations. Bereft of her closest familial and friendship ties in Korea, Ji-ah’s migration across the Pacific echoes a long history in which post-Korean war marriage migrants, adoptees, and mixed-race children gained legibility as American subjects via their uneasy incorporation into families across the United States. That is to say, the show’s gesture toward the emancipatory potential of Afro-Asian kinship relations is still limited by the elisions of more anti-imperialist political futures represented by characters such as Young-ja, whose untimely murder forecloses the possibility of representing Asian women as political agents in their own right.

Nonetheless, the narrative interventions embodied by Ji-ah’s character evoke new forms of queer, feminist Afro-Asian intimacy that are rarely represented in American mainstream media. Why is the character of Ji-ah able to forge such intimacy with Lovecraft Country’s Black American characters, in a way that was otherwise foreclosed in both Da 5 Bloods and Watchmen? Is there something particular about the Korean War and Black subjects’ relation to it — an earlier moment of inchoate possibility — that gets foreclosed by the time of the Vietnam War (which, it should be noted, South Korea joined on behalf of the US)? Were political divisions between the Civil Rights Movement and the internationalist Black radical tradition too entrenched by the Vietnam War era, collapsing the possibility of a more dialogical approach to Black politics? In some ways, Ji-Ah reproduces Cold War stereotypes of the Korean friendly: she aspires for incorporation into the American life represented in Hollywood films. In other ways, however, she exceeds Cold War politics: although located in South Korea, she is not invested in anti-communist politics per se, and even locates her most fulfilling friendship in Young-ja, the communist secret agent. Considering the fact that the Korean War is often called the “forgotten war,” it is notable that one of her kumiho powers is an ability to absorb the experiences of her Korean and American victims, making her a living archive of multiplicitous — albeit exclusively male — memories. While Ji-Ah arguably does not forward a clear anti-imperialist critique, her mutual love for Tic and his family exceeds a dichotomous and ultimately limiting Cold War framework, pointing towards a more queer and feminist form of Afro-Asian intimacy in the wake of the Korean War.

Articulating a queer, feminist, anti-imperialist politics of Afro-Asian solidarity is more pressing now than ever. This is a moment that the Council on Foreign Relations has balefully called “the End of World Order” — that is, the weakening of US military, economic, and cultural power — revealing how the convergences of anti-Blackness and US wars in Asia continue to haunt us today. This is also a moment of increased Asian American reckoning with our communities’ persistent anti-Blackness, prompted by the Black Lives Matters movement’s antiracist revolution. Representational politics, of course, will not save us. But cultural representations can point us toward queer, feminist, and anti-imperialist Afro-Asian possibilities and futurities. We draw inspiration from the images and narratives depicted in Da 5 Bloods, Watchmen, and Lovecraft Country, which present cultural blueprints for relating otherwise.