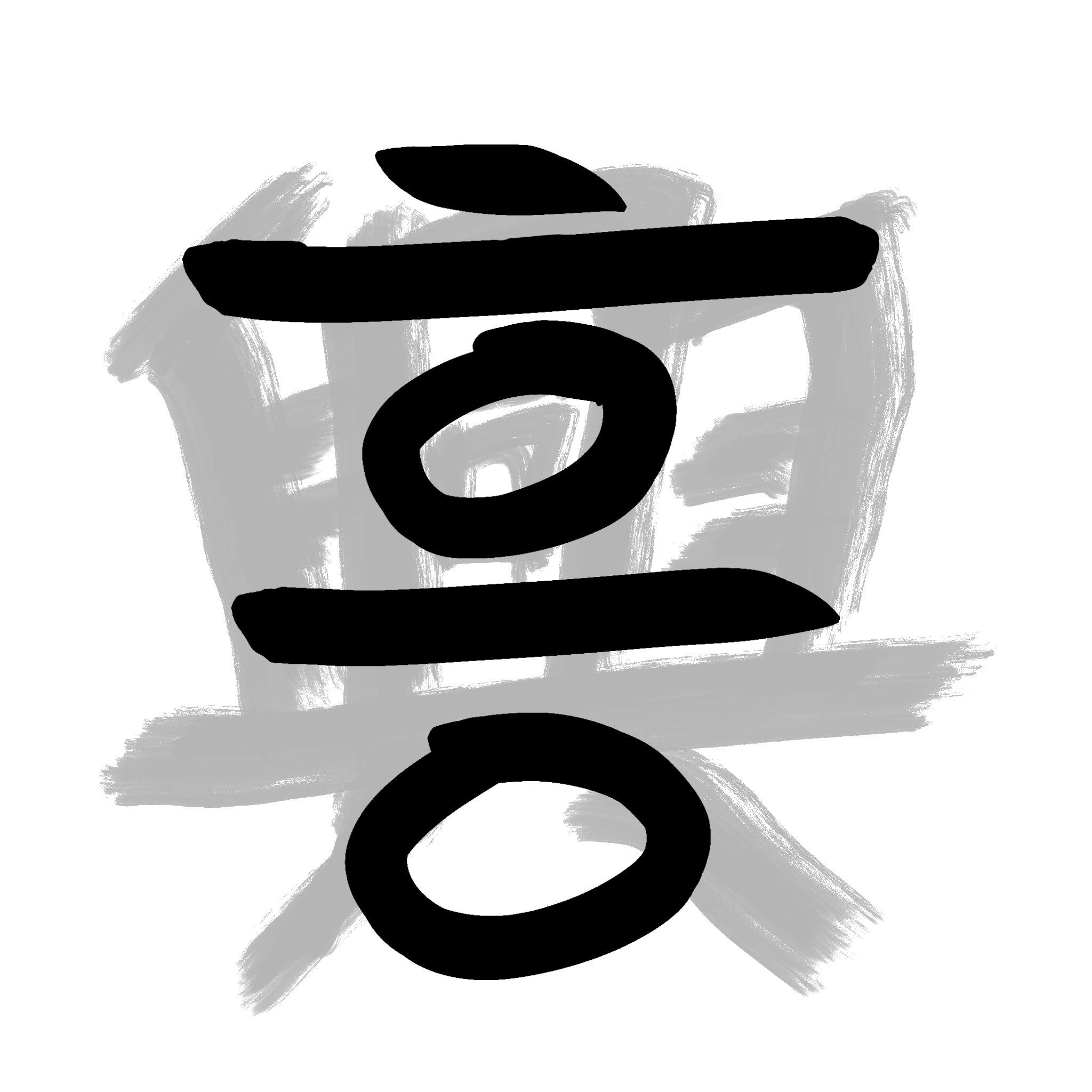

Heung | 흥 Coalition

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

︎ Instagram

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

Memories of the Strike: Who Killed the Movement?

Jun 12, 2021By: Soyo Nam

Edited by: Paige Morris

Collage by Grayson Lee

Seoul, South Korea

4:30 pm, Mar 31, 2005.

Flags, lots of white flags bearing black and bloody red slogans and affiliations like “the Flame of Minjung’s Liberation: Seoul National University Students Union” fly in a gentle yet chilly spring breeze. Sublime voices of protest songs about those who burned themselves to death in the struggle for Liberation in the ’80s make those still around feel guilty for being alive in this beautiful season. Students laugh and giggle, singing along to upbeat K-pop songs whose lyrics they’ve rewritten to challenge neoliberalism, the energy blooming alongside the colorful leaves of Gwanak Mountain.

Everybody shows up, even those old-timers who always used to study in the gray library building and complain about the “noise” from the Acropolis right outside their study space. Like a snowball, people roll in from over the hill and gather in the center of the Acropolis. Everyone can’t stop looking around. So many faces and hopes. The crowded air, suffused with the stench of cigarettes from the corner near the library where people gather to smoke, feels so fresh. Everybody wants to be part of this moment, scrambling to speak up, repeating the same excited words. I have never seen this big a crowd in the Acropolis before. . .

Around 1,700 undergraduate students filled “the Acropolis,” the symbolic venue of student activism at Seoul National University, for an emergency student union meeting to address the crisis facing public universities as a result of President Roh Moo-hyun’s neoliberal government and policies. Roh’s trajectory from a civil rights lawyer to the president of the state represented the hope and failure of the 86 Generation (’80s university graduates, born in the ’60s), who had always been proud of their student activism, which had contributed to Korea’s formal shift from an authoritative military regime to a civil government. Building upon this moral superiority, the 86 Generation consolidated their power by occupying high-level political and economic positions. Finally, they succeeded in making their representatives, Ahn Hee-jung and Lee Kwang-jae, the left and right hands of the 2003 president-elect Roh, officially becoming part of the machine.

Over the course of five years, Roh’s government: 1) passed a non-regular worker “protection” law that ironically accelerated an unprecedented mass layoff, pushing those who needed to be “protected” into the streets with empty hands; 2) sent Korean troops to Iraq to support U.S. imperialism in West Asia; 3) signed the Free Trade Agreement with the U.S., which jeopardized the livelihoods of Korean farmers; 4) and announced the neoliberalization of tuition fees in public universities. The regents of public universities jumped at the opportunity to raise tuition by 7.4%, 9.3%, and 7.3% in 2003, 2004, and 2005 respectively, with these increased rates being more than double that of inflation in those years: 3.5%, 3.6%, and 2.8%. Additionally, Roh’s government emphasized the importance of making Korean higher education globally competitive and asked universities to push students and researchers to work harder. Seoul National University, in particular, responded to this request by changing its grading system from absolute to curved. Against this backdrop of events, the student union at Seoul National University called the emergency general meeting, where they presented collective demands for a refund of the increased portion of the 2005 tuition, the abolishment of the curved grading system, and the establishment of a student-involved committee for managing the university. The meeting began legitimately by fulfilling the required quorum of 1,700 attendees based on a rough calculation of 10% of enrolled undergraduate students. Now was the moment, however, when union leadership had to grapple with the split between those who did and those who did not support direct actions.

7:20 pm.

It’s getting darker. Stage lights come on, illuminating the faces of the attendees, some of whom are starting to depart. Everyone can’t stop looking around at those ambiguous, disappearing faces of the masses, a huge contrast from the glaring lights onstage, where union officers stand. Once some members leave, concerns are raised about the quorum. We are not 1,700. We shouldn’t vote on the demands. This is UNDEMOCRATIC! A few union officers are nearly screaming, running around the attendees to agitate them. Other union officers confront them, forcing the agitators to leave and further scaling down the crowd. Although the union officers have already agreed that the quorum will only be required to begin the general membership meeting, the dissenting few intentionally use this question to cause confusion amongst rank-and-file members unaware of this arrangement.[1] Despite the doubts about the quorum, the members agree to vote, approving the demands.

8:30 pm.

Throughout the intense discussion on the quorum, more than half of the flags have disappeared. The remaining ones are completely still in the heavy night air. Soon, a handful of flags start to move against the current, leading the masses—can I still call them “the masses”?—from the Acropolis to the administration building to ask for the university president’s response to the students’ collective demands. The main entrance on the first floor is locked and heavily guarded by university police and staff. Still, several students manage to climb up to the third floor and break into the building by smashing the locks of the doors with hacksaws, hammers, and fire extinguishers. In the scuffle, a university policeman is injured and hospitalized. The student vanguards take control of the third floor and go down to open the main entrance, letting union officers and other members enter the building.

The director of student affairs from administration sits at the table with union officers. Thanks for sharing your concerns. I can’t promise anything for your demands since I am not a person in charge. I will let the president know. He is out of town and will be back on April 10. A non-response. Emergency meeting among union officers. What should we do? Leave with nothing or force the administration’s hand through direct action? The majority is inclined to leave the building and propose some moderate actions such as picketing outside. The officer from the social sciences department puts forth a motion to occupy the entire administration building, but the motion is not seconded. Nevertheless, several student militants make their own move, occupying the building again. A wildcat strike begins.

10:00 am, Apr 3.

The fourth day of the occupation. Students sit and lie on the floors of the long, narrow administration building hallways. Messy hair, in the same clothes, tired but still sharing a sense of humor, which makes that cold, flat, and firm floor feel a bit more bearable. The floor is also occupied by minjung-gayo books, essential for protest sing-along night; acoustic guitars, always, some of them missing the first string; markers; posters; and leftover chamchi-mayo dosirak—tuna again?—sent from supporters. Trying their best not to feel bored and lonely, the students in the halls speed through the slowly-passing time by reading, singing along, and making wall posters. New folks show up for the next shift, bringing today’s newspaper, the Daehak-sinmun. What does it say? Some bullshit. Look at the editorials. The title of one says: “WE DEPLORE THE UNDEMOCRATIC BEHAVIOR IN THE EMERGENCY GENERAL MEETING.”[2]Critiques of the occupation start to circulate, most coming from the right-wing student faction and the university-sponsored Daehak-sinmun.

What is interesting about the newspaper is that its creators pretend to be neutral or impartial, claiming they are representing apolitical and ordinary students—il-ban-hak-woo—and disguising their right-wing politics and close ties with administration. They underline the necessity of the democratic process to collect the voices of this apolitical majority. The dichotomy between political and apolitical assumes the former as something “impure” that has a “bad” intention, such as brainwashing the “pure” and apolitical majority. Based on this dichotomy, the first condition for democracy is to be apolitical. The current occupation with an anti-neoliberal slogan is political, therefore “undemocratic.”

Above all, this occupation is “undemocratic” since it violates the formal requirement, the quorum of 1,700. This quorum was applied only to begin the meeting, not during the voting process. As absurd as it sounds, even the union officers agreed on these terms beforehand. Therefore, despite all confusion and conflicts, it is clear that the emergency general membership meeting “formally” fulfills the requirement. Which begs the question: Is it really about “formal” democracy or something else? Why do these right-wing students and the university press not apply the same criteria to administration? The “undemocratic” occupants are asking for students’ participation in the committee of university operations, which have been exclusively controlled by a few professors, businessmen, and government officials. Is democracy really at stake in their critique of the occupation?

Despite the lack of direct support from union leadership, the occupation lasted for 20 days, until April 19. Union officers finally had a meeting with the university president. No substantial changes were promised.[3] There was no reason for the president to promise anything, as the strike was already over. The students who led the occupation were suspended for an indefinite period of time. However, the specter of the strike did not disappear. In 2011 and 2017, every six years, the administration building has been occupied by different students with the same slogan, fighting against the neoliberalization of public universities. Memories remain.

Ancestral, traditional, and contemporary lands of the Anishinaabeg and Wyandot peoples—also known as the city of Ann Arbor, Michigan

5:30 am, Sep 8, 2020.

A heavy downpour, a not-yet-bright but early morning. A handful of picketers gather at one of the construction sites in front of the University of Michigan’s Ruthven building. They are already soaked to the skin even before starting their picket shift. It feels so fresh, though. Like when you go out for an intentional run in the heavy rain to break out of your lethargy. Hey folks, thanks for showing up. I am your picket captain today. What we are going to do is to circle around this entrance of the construction site. While circling, please keep six feet distance from each other. Ah, also, please don’t forget to check-in through this QR code, it’s for contact tracing. Anyways, I prepared some chants, it goes like… sorry my glasses are too foggy with this mask. By the way, can anybody drum this bucket?... Okay, then I can do it. Please repeat after me. (BOOM) SAAAAAVE (BOOM) OUR (BOOM) HEALTH, (BOOM) NOOOOOT (BOOM) YOUR (BOOM) WEALTH. . .

Nobody is here yet, just picketers. But we chant and shout so seriously as if confronting hundreds of construction workers. After thirty minutes of shouting in the dark, several construction workers arrive in their pickups. Staying inside, they wonder why the heck these fanatics in red and purple shirts are circling around in the pouring rain at six in the morning. HOT OR COLD, RAIN OR SHINE, YOU DON’T CROSS A PICKET LINE! Finally, the workers understand what’s going on. Some get out from their pickups to ask our affiliation and say they are also unionized. After the conversation, they go back to their vehicles with the headlights on, and leave the construction site. Some pickups pass by picketers, honking cheerfully.

The members of the Graduate Employees' Organization (GEO) went on strike, asking the admin for safe and just responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was one of the first abolitionist strikes in the U.S. that addressed the intersections of race with pandemic-related labor issues.[4] Some of the demands were: the universal right to work remotely, cutting ties between the Ann Arbor Police Department (AAPD) and the Division of Public Safety & Security (DPSS) at the University, and defunding DPSS to reallocate its budget towards community programs. These demands delved into the meaning of “safety” in myriad forms: not only in the midst of the pandemic but also in the face of systemic racism.

After George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the police, ICE’s threats against international students who were desperately flying back and forth between the U.S. and their home countries, and the university president’s repeated refusal to communicate with community members about implementing adequate pandemic responses, growing collective resentment fueled organizing within GEO. In May, GEO rank-and-file members created the COVID Caucus and wrote an open letter asking for a more active response to the pandemic and racial discrimination. The letter was signed by more than 1,700 graduate workers, faculty allies, and community members. The COVID Caucus organized various meetings and protests before the semester began. As administration did not show any substantial change and continued to ignore the needs and concerns of graduate workers and community members, several rank-and-file members proposed that the union prepare to strike. However, union leadership was reluctant to send a strike ballot unless there were enough strike pledges. Based on the previous strike experiences, some officers suggested 800 pledges out of approximately 2,100 members, not as a condition to decide whether the union would go on strike, but as a precondition for sending strike ballots to all members. More pledges and commitments to work stoppage would have indeed guaranteed the success of the collective action and reduced the risk of retaliation from administration. However, getting 800 pledges was extremely challenging given the unfavorable circumstances: it was the first summer of the COVID-19 pandemic, and everyone was dispersed and quarantined in different states and countries. Despite the enthusiastic work done by some rank-and-file members, we were short more than 200 pledges. Union leadership, leaving the task of organizing to other members, repeated the same argument: 800 pledges or no strike ballot. For them, 800 was the “statistically objective” number that represented the majority. Meanwhile, the semester was about to begin with only a “non-major action” planned.

Suddenly, the situation changed on August 28. The faculty senate held an emergency meeting to discuss the possible motion of no confidence in the university president regarding his pandemic responses. Witnessing the faculty’s anger against administration, union leadership flipped their unwillingness to engage in a work stoppage. The number 800 in which they trusted was no longer at stake. It was ironic that union leadership paid more attention to the concerns of faculty, who are at the top of the university hierarchy, than to those of their fellow graduate workers.

Despite the lingering hesitancy among the union leadership on some strike demands such as defunding DPSS, almost a thousand grad workers, the largest number of attendees ever in the history of GEO, showed up for the general membership Zoom meeting on September 4. Many attendees indicated that this strike should not only be for the benefit of the union members but must also address the structural racism revealed more explicitly by the pandemic. However, some union officers, who were in close conversation with administration, made their last attempts to demoralize the movement toward collective action. They tried to derail the conversation on the strike by suggesting an improved communication channel between the union and administration. As this proposal did not substantially address the demands for the universal right to work remotely or the defunding of the police, the attendees decided to steer the discussion again toward striking and agreed to send the strike ballot out to all union members. The voting results were revealed on September 7: 79% of voters in favor. GEO went on strike from September 8.

The strike was timely and historically meaningful because of its struggle for the common good, beyond merely seeking technical changes in the language of contracts. We were fighting for a safe campus, but also a racially just community. The union has traditionally been a white-majority union, and it still is. However, I remember Black, Brown, and Asian rank-and-file members who until then had not been strongly active in the union deciding to show up on the picket line. I saw them again and again, every day. While many BIPOC rank-and-file members were chanting on the picket line, some union officers who rarely showed up at the strike brought around a proposal from administration that intentionally ignored demands related to racial justice, claiming that it was “non-negotiable.” Despite the continued attempt at demoralization from some GEO officers and threats of retaliation from administration, union members continued to support extending the strike repeatedly.

7:30 pm, Sep 16.

Around September 16, undergraduate resident staff was organized and about to go on strike in support of GEO, the faculty senate was about to approve the vote of no confidence in the president of the university, and above all, a lot of new graduate workers joined the union in support of the strike.

Another emergency general membership meeting was held to decide whether to continue striking. As the strike had lasted longer than a week, university administration escalated their threat by announcing that it would file a lawsuit against the union for stopping university operations. On the other hand, administrators promised some changes to address the union demands, although they did not address the demand to defund the police. In this last meeting, coming up against this two-faced strategy from admin, union leadership officially recommended stopping the strike and accepting the proposal. Only a few officers spoke up against this recommendation. In a crucial moment, a Black member of the newly created emergency anti-policing working group spoke up, supporting union leadership’s recommendation to end the strike. This opinion was received in such a way that it seemed to represent the opinion of all BIPOC community members—one minority voice outweighing other minorities—leading more majority attendees to feel comfortable expressing their concerns about the strike being “radicalized” beyond the ambit of trade unionism. Predictably, the white majority union highlighted an individual minority who supported the majority’s moderate politics.

In the same way, the University of Michigan has promoted so-called “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI),” promoting underrepresented minorities’ individual academic achievements instead of addressing the fundamental issues of structural racism. Despite the numerous university announcements highlighting its commitment to DEI, racist incidents repeat every year on campus. DEI is not about the university’s structure, but representation. I wonder: what is necessary to grapple with structural racism? Increasing the number of BIPOC students admitted and promoting those several brown faces on the homepage of the school’s website? Or abolishing policing on campuses so that BIPOC students and workers do not need to tiptoe around armed DPSS officers?

The decision to end the strike—a decision “legitimated” by an individual minority member—brought the soaring momentum of the movement for a broader university community to a halt.

6:00 pm, Jan 31, 2022.

A year and a half after the pandemic strike. Still in a Zoom room, virtually joining a general membership meeting. Headphones on, as if listening to a podcast, I take clothes off a drying rack and start to fold them. It is not because I want to save my time by multi-tasking. Nor because I wish I were with everybody in person. Something has been missing. Maybe it’s because I have not been active enough to be looped into the post-strike conversation. There has been no forward movement in my processing of the strike. Nobody’s fault. Just moving on. The bargaining year is approaching.

In this meeting, the union needed to prepare “narratives” that would clarify and justify the suggestions and demands for a new contract. The leadership suggested five narratives: “Accessibility,” “Affordability,” “Health,” “Toward a Public University,” and “Burnout.” It was no coincidence that the discussion went between “Affordability” and “Toward a Public University,” as “Affordability” represented the narrative of those who wanted to keep the union’s demands within the “permissible” range (e.g., salary, benefits) from the administration’s perspective, whereas “Toward a Public University” represented those who believed that the union’s mission is not limited to the benefit of the majority of its members. The attendees of the general membership meeting spoke up and shared their comments on the Zoom chat. Although the discussion did not become explicitly combative like the conversations during the strike, I could feel the tension through my laptop screen and speaker. Twenty minutes later, the voting link was sent. The majority voted on “Affordability.” “Toward a Public University” was not chosen.

The implication of this “democratic” choice based on the logic of numerical majority is not clear yet, as the development of the bargaining platform has just begun. It will depend on how we translate this choice into concrete demands. However, one thing clear to me was that the gap between “Affordability” and “Toward a Public University” indicates the discrepancy in members’ understanding of the purpose of the union.

A union is an organization established on the basis of the agreement of a specific group of workers. In this sense, some might say that a union exists only for its exclusive members. Your union will not save the world, but it can help you out if you are paying your dues. True, a union is not a political party nor a militant organization. Nevertheless, unions are the fundamental base for social movements, as they stand on the frontline between labor and capital. The contract, through which employees and employers define their relationship, is one of the most important documents that explicitly demonstrates what is at stake between labor and capital and what their current priorities are. What unions do always has an effect beyond their ambit, not to mention their influence on fellow unions’ strategies. That is why now all eyes are on the Amazon labor union in Staten Island, New York. We feel that the current union organizing efforts in the core of U.S. tech-commerce capitalism will have a significant impact on our lives regardless of the distance between us.

Acknowledging this intertwined relationship between unions, community, and society, many unions explicitly highlight their objective for social progress in their constitutions. For example, the GEO constitution recognizes social progress as one of the main objectives, defining it as follows: “To cooperate with other segments of our society and with other labor organizations in particular for the achievement of common goals.”[5] The problem is that this objective becomes less prioritized when the bargaining comes up. As union members, do we really pursue values for social progress, such as justice? True justice will be achieved when our values, such as “affordability,” “accessibility,” and “health,” are not limited to union members, and are not contingent on a certain number. From the standpoint of a realist at the bargaining table, this can sound too naïve and idealistic. What matters for the union is merely a number, and that is what kills the movement before it has the chance to live.

Whether in Seoul or Ann Arbor, whether more than a decade or only a year ago, the conversations at the bargaining table would be the same. Once you come to this table, you should respect the rules of the game. It’s about money, not politics. Since the dichotomy between the political and the economic emerged and was widely accepted with the rise of narrowly-focused economics in the twentieth century, the term “political” became a persona non grata, a degenerated name that should not be mentioned. Political demands, such as student-involved university management and anti-policing initiatives, are “not permissible,” whereas economic demands about student well-being, benefits, and wages became the core of the negotiation and contract. It is because economic demands are considered quantifiable. In contrast, it will require tremendous time, effort, and commitment to translate our political hope for anti-neoliberalism and racial justice into contract terms. The existing contract framework will also need to be changed substantially given its presumption of the division between the economic and the political. The political nature of economic demands and the economic base of political demands should be considered beyond this dichotomy. In this sense, what is at stake is not whether anti-neoliberalist and anti-racist demands are political or economic problems. The true goal is building a common understanding of the necessity and possibility of concretely materializing those demands.

The complex nature of this task does not mean that political demands are impossible, abstract, idealistic, and naïve. The point is that these demands make the majority uncomfortable. Smiling from their comfort zones will not be enough of a response to a demand that asks them to reimagine the status quo, to restructure familiar institutions. The silent majority’s kind and friendly faces will contort when confronted with the real work that must be done and the weight of it on their shoulders. In this sense, we, the strikers in Seoul and Ann Arbor, were realists. We pursued what was possible and necessary. Our hope was concrete, more objective than any number.

[1] Some details of the strike at Seoul National University are based on the SNU Press article: http://www.snunews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=2251, Accessed Apr 26, 2022.

[2] http://www.snunews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=2246, Accessed Apr 26, 2022.

[3] http://www.snunews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=2406, Accessed Apr 26, 2022.

[4] https://jacobinmag.com/2020/09/university-michigan-graduate-workers-strike, Accessed Apr 26, 2022.

[5] The GEO constitution is available at the following link: https://www.geo3550.org/about/constitution/, Accessed Apr 26, 2022. Currently the GEO is in the process of revising its constitution due to some outdated language, so the language may have changed by the time this essay is out.