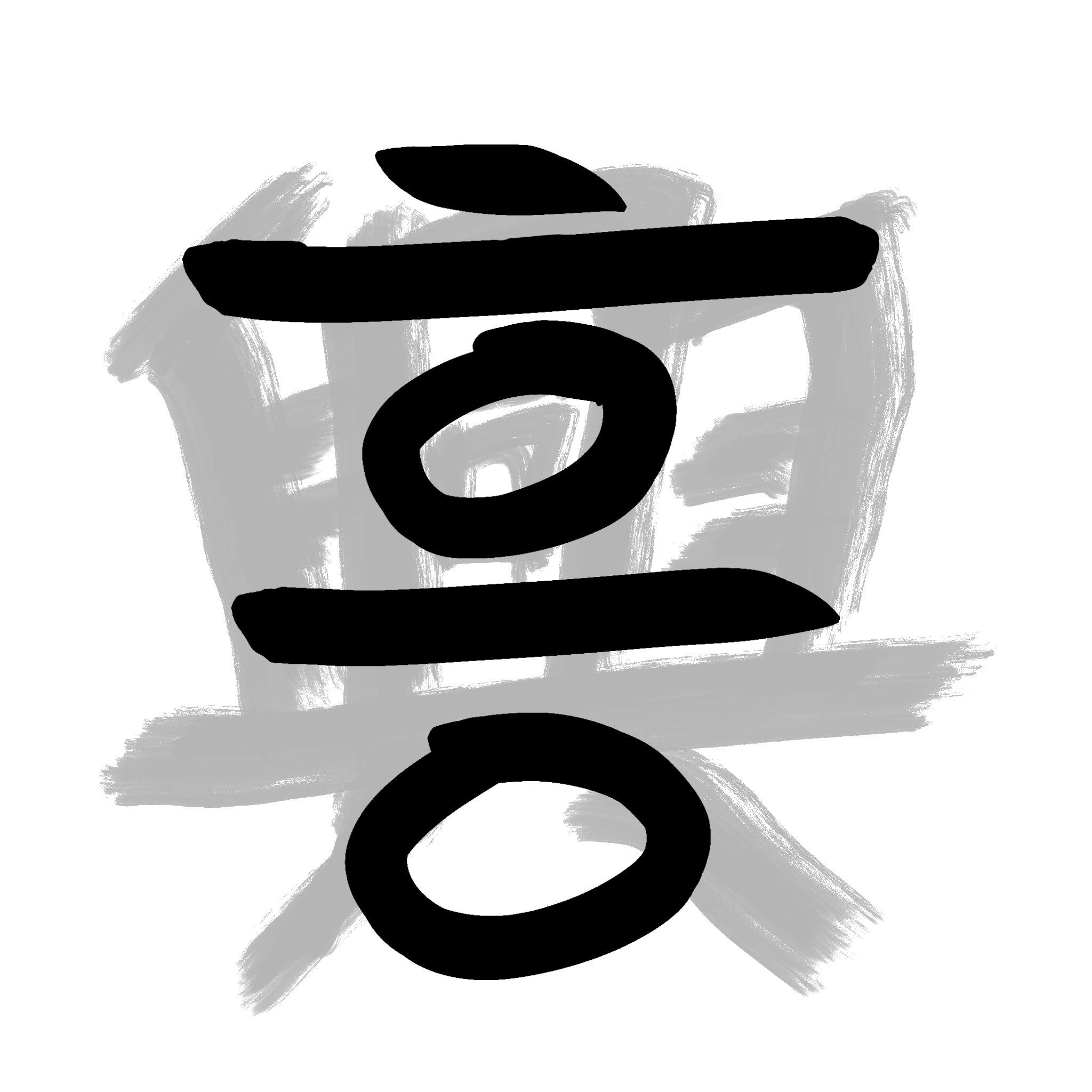

Heung | 흥 Coalition

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

︎ Instagram

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

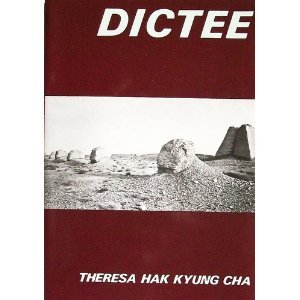

“Inside the Eclipse”: DICTEE and Revolutionary Times, or the Times of Revolution

October 12, 2020

By: Kris Shin

Edited by: Rachel Min Park

The first encounter I had with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s DICTEE helped me think through and sit with the discomfort and trappings of identity. Comprised of nine sections for nine muses, DICTEE has been read and taught across various disciplines and contexts, and is regarded as an avant-garde work of Asian American literature. The much discussed hybridity of its montage-like form seems the perfect container for the ambivalence one might feel about occupying a space that is neither this nor that. But unlike many other works by Korean-American or Asian diasporic writers, DICTEE appears uninterested in serving a frictionless fantasy of assimilation. It does not center a story about an immigrant successfully integrating into American culture, thereby becoming a free individual or subject, nor does it present an immigrant’s failure to assimilate as tragedy. While taking on aspects of autobiography, the collage-like format of the work complicates and multiplies the self, making the self permeable to other voices, eyes, ears, and tongues. The work is transnational, spanning languages and locations with text appearing in English and French, as well as images of Hangul and Chinese characters. DICTEE doesn’t take immigration for granted, and instead points to the reasons why a nation would be destabilized, resulting in immigrants, refugees, and exiles. It laces across its pages a history propelled by imperialism and colonialism. As such, reading DICTEE made me interrogate the aspiration to belong. The series of questions goes: belong to what? To the U.S.? To Korea? And should one choose to occupy the space that is “Korean-American,” what must she give up or betray to “belong” as an American? If the costs are too horrendous and predicated upon the unfreedoms of another, should we not, then, search for alternatives, to perhaps pledge our allegiance to something other than a state that arbitrarily excludes and includes?

The first encounter I had with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s DICTEE helped me think through and sit with the discomfort and trappings of identity. Comprised of nine sections for nine muses, DICTEE has been read and taught across various disciplines and contexts, and is regarded as an avant-garde work of Asian American literature. The much discussed hybridity of its montage-like form seems the perfect container for the ambivalence one might feel about occupying a space that is neither this nor that. But unlike many other works by Korean-American or Asian diasporic writers, DICTEE appears uninterested in serving a frictionless fantasy of assimilation. It does not center a story about an immigrant successfully integrating into American culture, thereby becoming a free individual or subject, nor does it present an immigrant’s failure to assimilate as tragedy. While taking on aspects of autobiography, the collage-like format of the work complicates and multiplies the self, making the self permeable to other voices, eyes, ears, and tongues. The work is transnational, spanning languages and locations with text appearing in English and French, as well as images of Hangul and Chinese characters. DICTEE doesn’t take immigration for granted, and instead points to the reasons why a nation would be destabilized, resulting in immigrants, refugees, and exiles. It laces across its pages a history propelled by imperialism and colonialism. As such, reading DICTEE made me interrogate the aspiration to belong. The series of questions goes: belong to what? To the U.S.? To Korea? And should one choose to occupy the space that is “Korean-American,” what must she give up or betray to “belong” as an American? If the costs are too horrendous and predicated upon the unfreedoms of another, should we not, then, search for alternatives, to perhaps pledge our allegiance to something other than a state that arbitrarily excludes and includes?These are only some of the questions that sprout and blossom as I slowly (re)read and think about DICTEE. One that increasingly grasps my attention is the question of time, especially now when ongoing crises have only intensified with the events of this year. Without drastic action (or in the case of degrowth, a drastic cut in certain actions), environmental collapse and the resulting and continued violence against refugees/migrants looms on the horizon. Meanwhile, countless movements against state violence have erupted worldwide. Police brutalize protestors, whether in the U.S., Belarus, Hong Kong, Chile, Indonesia, or Egypt. Even as we face multiple crises, many are expected to (and will) march to work, financially stratified, while the incarcerated and unemployed face evictions, isolation, illness, and/or death (murder by the states that espouse such dangerous hogwash like “herd immunity” as a sensible policy measure to address the COVID-19 pandemic). All of it seems more than a little absurd. Mostly, it is infuriating.

The crises of the present remind me of certain scenes in DICTEE. In the chapter titled MELPOMENE/TRAGEDY, Cha’s narrator notes the experience of becoming an American citizen:

I have the documents. Documents, proof, evidence, photograph, signature. One day you raise the right hand and you are American. They give you an American Pass port. The United Sates of America. Somewhere someone has taken my identity and replaced it with their photograph. The other one. Their signature their seals. Their own image. And you learn the executive branch the legislative branch and the third. Justice. Judicial branch. It makes the difference. The rest is past.

The only thing separating Cha’s narrator from a migrant or refugee are these documents, these sheets of paper that signify she is a “legitimate” citizen in the state’s eyes. When Cha’s narrator returns to Korea, she refers to herself as “You,” as if to indicate dissociation and a splitting of self:

You return and you are not one of them, they treat you with indifference. All the time you understand what they are saying. But the papers give you away. Every ten feet. They ask you identity. They comment upon your inability or ability to speak. Whether you are telling the truth or not about your nationality. They say you look other than you say. As if you didn’t know who you were. You say who you are but you begin to doubt. They search you. They, the anonymous variety of uniforms, each division, strata, classification, any set of miscellaneous properly uni formed. They have the right, no matter what rank, however low their function they have the authority. Their authority sewn into the stitches of their costume. Every ten feet they demand to know who and what you are, who is represented. The eyes gather towards the appropriate proof. Towards the face then again to the papers, when did you leave the country why did you leave this country why are you returning to the country.

For Cha and countless others, immigration wasn’t necessarily a matter of choice. The Japanese occupation (from which Cha’s family initially fled to Manchuria) and the Korean War tore families apart, scattering them, and brutally squashed many lives. After overthrowing Japanese colonial rule, it seemed as if self-determination was in reach. However, the U.S. and the Soviet Union split Korea in halves. The war technically continues to this day, as no peace treaty was ever signed. The tragedy is this wound, this separation which Cha locates in language and in/articulation. Just as the documents legitimize Cha as an American national to the U.S., the papers also serve as “proof” of difference and other her, though they are a result of a fiction, that fiction called a border. Cha is “[n]ear tears, nearly saying, I know you I know you, I have waited to see you for long this long.” Those she finds familiar, those she desperately wants to be recognized by, dismiss her. What horrors await those who don’t even have those papers?

Police and state violence configure the histories presented in DICTEE. In the same chapter, Cha’s speaker addresses a letter to her mother. Cha returned to Korea in 1979 and then again in 1980 with her brother to work on her film, White Dust from Mongolia. After the assassination of the dictator Park Chung-hee, there was much political unrest as the next military dictator-to-be, Chun Doo-hwan, expanded martial law across the nation enforced by troops. In May 1980, the Gwangju Massacre/Uprising occurred. Chun justified martial law by pointing towards North Korea and communist sympathizers as threats. Cha and her brother were harassed by South Korean authorities during their stay who suspected the siblings of being North Korean spies. In the letter Cha writes:

Here at my return in eighteen years, the war is not ended. We fight the same war. We are inside the same struggle seeking the same destination. We are severed in Two by an abstract enemy an invisible enemy under the title of liberators who have conveniently named the severance, Civil War. Cold War. Stalemate.

A sense of despair marks her words. She is “inside the demonstration,” “locked inside the crowd and carried in its movement.” There is a lack of agency in her movement, almost like being caught in the onslaught of time. The crowd is tear-gassed. The violent sensory experience triggers a memory of her brother in his student uniform about to join a demonstration while the speaker’s mother begs him not to go as soldiers are killing students. In that memory, it is 1962, a year after Park Chung-hee’s coup. But in the time of the letter, Cha writes, “I am in the same crowd, the same coup, the same revolt, nothing has changed.” The words hold an ambivalence about history, about the inevitability of it repeating. So, too, is there an ambivalence about history’s martyrs who are made “an animal useless betrayer to the cause to the welfare to peace to harmony to progress.” But if there is a pessimism about history in that ambivalence, there is also the desire to “kill the time that is oppression itself” and “[t]ime that delivers not,” a desire against “imaginary borders. Un imaginable boundaries.”

***

In thinking about inclusion/exclusion, belonging, history and time, I am occupied by the image that Cha leaves us towards the end of DICTEE: “Tenth, a circle within a circle, a series of concentric circles.” In contemplating this image, I am drawn to other images within the book. In the chapter TERPSICHORE/CHORAL DANCE, Cha’s narrator addresses a “You” that waits for a dandelion seedling to grow, for its “entire flower to burst and scatter without designated time, even before its own realization of the act, no premonition nor preparation. All of a sudden. All of a sudden without warning. No holding back, no retreat, no second thought forward. Backwards. There and not there. Remass and disperse. Convene and scatter.” What is time to the dandelion seedling? What is waiting without time? If we do not ascribe a teleology or instrumental purpose to the life of a dandelion seedling, then one might see the burst of its flower as a spontaneous movement and not an inevitable and self-evident picture of “progress,” “growth,” and “function.”

Progress and growth, the hymns (or commercial jingles) of states around the world, have been heralded as some kind of universal good. But what is often imagined as progress, such as technological development or the constant accumulation of more capital, leads to exploitation, domination, destruction. Profit for a few, sure. But when one speaks of progress, one must ask, “Progress for whom?” The question of cost is implicit. Along with progress and growth, states adopt a linear view of time in order to carry on business as usual. We are, according to the story, more advanced and progressive than we’ve ever been; progress is inevitable, is surely the end we’re headed towards.

The word revolution originally derived from the Latin revolutio which referred to the movement of celestial bodies, such as the Earth revolving around the sun. The word originally held something of the inevitable, of things “turning back” to the way they were, restoring harmony. The circle, the figure of revolutions, is turned into a clock, sectioned off into hours and minutes, constantly ticking. Most of those hours we spend at work. We look at the clock, wondering when the work day ends. Exhausted, we go home and wait for the weekend to recuperate. Some of us don’t even have that “time”—time to rest, time that we think we spend actually alive, to pursue our creative urges or to simply do things for their own sake whether those things are “productive” or not. We are told the solutions are to manage our time, to forego sleep and rest, to eat those meal replacements or forget the meal altogether, cut down on contemplation or doing nothing which is to “waste time.” Two revolutions of the clock’s hands. The cycle repeats. This is hardly the kind of revolution we asked for.

***

In his essay, “On the Concept of History,” Walter Benjamin, himself a Jewish refugee, critiques the concept of progress itself, as packaging humanity’s history as one of progress is painting it as a “progression through a homogenous and empty time.” This homogenous and empty time is the time of clocks. One hour has the same measure, is interchangeable with the hour of the next day. This homogenous, empty time is the time of boredom, a time that passes, a time that wears us out. It is the time of capital. In contrast, what Benjamin calls “messianic time” is a filled time. It is a time of immediacy, a revolutionary time. In Theses XV, Benjamin writes, “The consciousness of exploding the continuum of history is peculiar to the revolutionary classes in the moment of their action.” He recounts an event during the July Revolution “which did justice to this consciousness.” Those protesting shot at clock-towers throughout Paris, as if to stop time. Within these seemingly absurd or ineffectual actions were the seeds of alternatives. At the very least, the protestors expressed a desire for something other than the existing order. The moment crystallized a sense of possibility.

Circling back to Dictée, in the same TERPSICHORE chapter, Cha writes:

Full. Utter most full. Can contain no longer. Fore shadows the fullness. Still. Silence. Within moments of. The eclipse. Inside the eclipse. Both. Fulmination and concealment of light. Imminent crossing, face to face, moon before the sun pronounces. All. This. Time. To pronounce without prescribing purpose. It prescribes nothing. The time thought to have fixed, dead, reveals the very rate of the very movement. Velocity. Lentitude. Of its own larger time.

The image of the eclipse evokes a different kind of time, perhaps even messianic. It is a “larger time” that gestures to a wholeness that both contains and conceals darkness and light. A celestial event that cannot be repeated the next day, it suggests a cyclical or even cosmic model of time as opposed to a linear one. The eclipse, thus, illustrates a moment of immediacy, a time where past, present, and future converge. A disturbance in placid skies.

COVID-19 brought certain parts of the world to a halt. The fortunate may well have continued life as before minus access to specific consumer activities like concerts, travel, or dining out. Amazon boasted record-high earnings and other big corporations similarly profited or were bailed out as unemployment rates skyrocketed. Many of the institutions that structured our daily lives crumbled. Friends and strangers mentioned the warped temporality of this year under lockdown, how it felt like they had aged a decade. People lost track as days bled into each other. Schools closed or moved online. The states that did not provide adequate aid and did not take appropriate action in time set the grounds for revolt. A rupture formed and protestors and activists seized this moment of crisis. Abolitionism entered mainstream conversation. People were shown the possibilities of a temporality not structured around growth for profit’s sake. Protestors lived revolutionary time as they set police stations ablaze for the countless victims of murderous cops, as they took down monuments to slaveowners and colonizers, as they looted and distributed essential goods to those in need or took what they had long had been denied, as they seized empty buildings to shelter what would be a community (however tenuous and temporary), as they danced and sang and taught each other while masked, showing a concern and regard for each other’s lives that the state had not.

“When does a crowd become a collective? Somewhere along the lines, perhaps the crowd or community asks: What binds us? What is the center we share? The answers are vital if we are to wonder how the disenfranchised and dispossessed may build solidarity across borders. ”

When does a crowd become a collective? Somewhere along the lines, perhaps the crowd or community asks: What binds us? What is the center we share? The answers are vital if we are to wonder how the disenfranchised and dispossessed may build solidarity across borders. Nationalist myths tend to fixate on purity, on who gets to belong/is a “legitimate” citizen and who is the enemy/other. Essentialisms suggest that there are fixed and unchangeable qualities about a country’s people or a certain demographic. Such narratives are the ideology behind extremes—genocide, caste systems, white supremacy, segregation, policing. These ideologies, alongside material conditions, fuel movements that seek to expunge all differences by centering one group at the expense of others. Facing the discomfort granted by challenging easy myths and essentialisms that offer the illusion of wholeness is the beginning. Here we might think of the image Cha left us of “a series of concentric circles.” The circles we draw do often exclude. But broadening that circle, that embrace, is key to building movements. There is no “I” without an “other” and the other is always within the I. If our shared centers can’t be found in nationalist or essentialist narratives, perhaps they are located in the way a polished apple nestles in many hands along the supply chain before it lands on someone’s table to nourish another, or the way the apple is left to rot as supposed surplus in a dumpster while mouths hunger.

Sources and Miscellanea

- Cha, Theresa Hak Kyung. DICTEE.

- Benjamin, Walter. “On the Concept of History”

- Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (March 4, 1951 - November 5th, 1982) was raped and murdered a week after the publication of DICTEE. I did not want the fact of her violent death to steal away the focus on her work, though I also didn’t think it should go unmentioned. I wish I could tell her in person or in a letter how much her work meant to me and so many others, how it continues to glimmer and give with each reading and viewing. Her voice still feels alive.

- On degrowth.

- “Who Knows Where the Time Goes?” - Fairport Convention

- Kim Jung Mi’s album NOW When this album was released in 1973, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha would have been 22, a student at the University of Berkeley. I don’t know if she ever listened to this album. But I think of how the album was banned under the Park Chung Hee dictatorship and how Cha’s family, too, was connected to that history. The utopian quality of the lyrics to “Haenim (햇님)” haunt me as a voice from the past that speaks of a future that has yet to arrive.

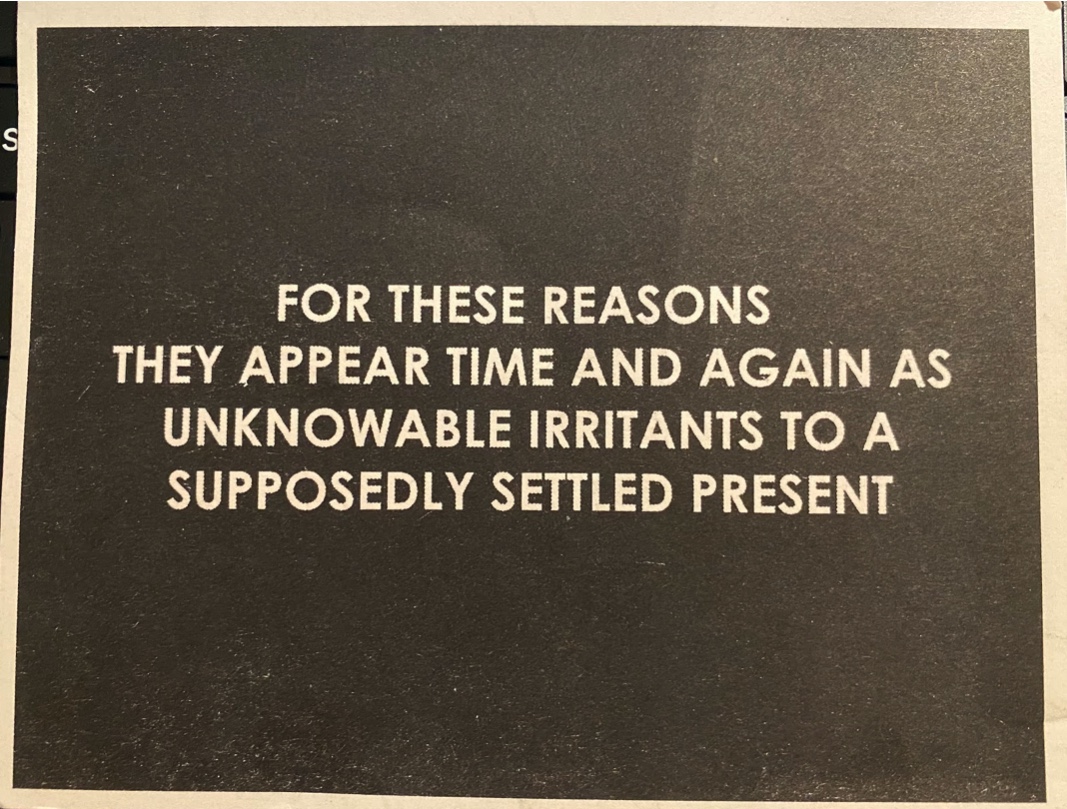

7. Selected by Jerome Reyes for the exhibition Way Bay, BAMPFA (2018)The card says the quotation is from Jeff Chang’s “Who We Be: The Colonization of America” (2014). The actual title of the book is “Who We Be: The Colorization of America” but, whether intentional or not, I found that Jerome Reyes’s use of “colonization” instead gave a different context to the quote, gesturing towards America’s history.

8. An exercise: Record yourself reading a chapter or segments of Dictée. Read until your throat becomes parched, until you capture the hoarseness of your own voice. Listen to the recording. Listen to where you stumble and stutter, where your tongue seems to trip over itself. Listen towards sleep.