Heung | 흥 Coalition

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

︎ Instagram

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

Against Martyrdom: The Legacy of Jeon Tae-il and Notes on Collective Organizing

August 13, 2020

By: Rachel Min Park

Edited by: Sophie Bowman

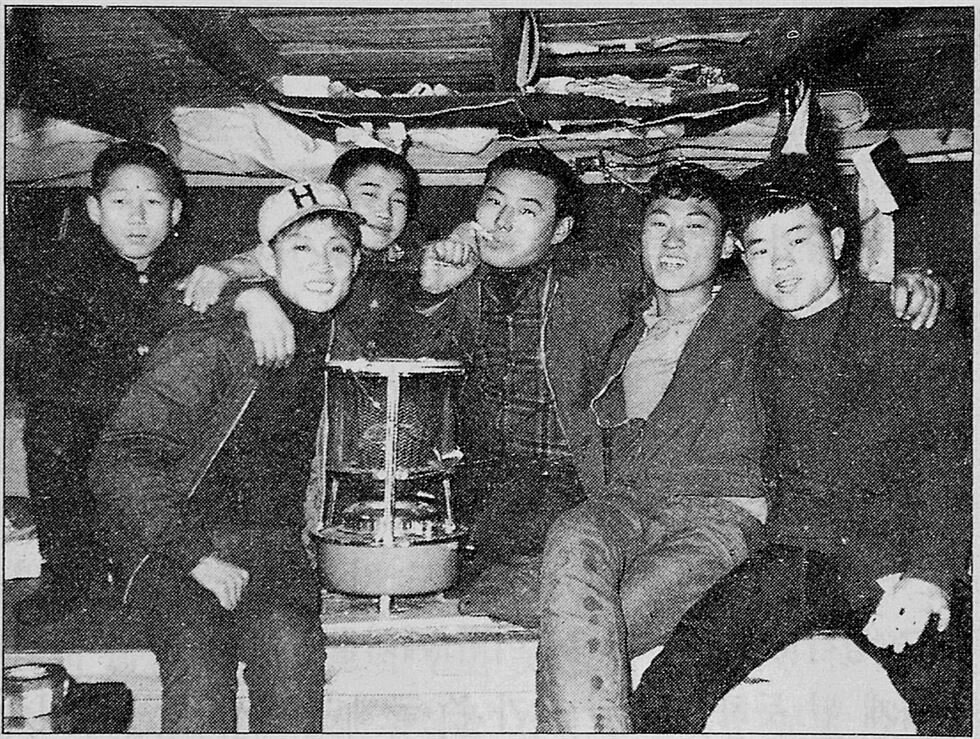

Labor activist Jeon Tae-il, first from right, with his comrades in 1967 / Korea Times file

Note: The following article contains mentions of suicide. For additional information on Jeon Tae-il, along with a contextualization of protest by suicide, please see the Working Class History Podcast’s transcript here.

On November 13, 1970, in the middle of a turbulent protest at the Pyeonghwa Market, Jeon Tae-il sprinted to the front of the demonstration and shouted his now-famous last words: “Workers are not machines!” “Guarantee the Three Basic Labor Rights!” “Do not let my death be in vain!” Proceeding to set himself on fire, Jeon died shortly afterwards from his grave injuries, but his story and legacy has continued to live on. 2020 marks the 50th year since Jeon Tae-il’s self-immolation to protest the poor working conditions in South Korean factories and sweatshops, yet the endless litany of laborers’ deaths has persisted—bittersweetly reminding us both how far the labor movement in South Korea has progressed since his death, as well as how far there is left to go.

A mere 22 years old at the time of his death, Jeon has since become a celebrated martyr and icon for the South Korean labor movement. His death has inspired the creation of numerous institutions and artworks commemorating his memory, such as the Jeon Tae-il Memorial Foundation (founded in 1984, it also grants the Jeon Tae-il Literary Award and the Jeon Tae-il Labor Award), the erection of a statue above Cheonggyecheon in Seoul (where most of the textile factories were located), the film A Single Spark (Areumdaun cheongnyeon jeon taeil, dir. by Park Kwang-su, 1995), a best-selling biography by Jo Yeongrae (Jeon taeil pyeongjeon, Dolbegae Press, 1983), and even a musical (Taeil, 2018).

Born in 1948 to an impoverished family, Jeon and his family briefly lived in Seoul before moving back to his hometown of Daegu in 1960. His father forced him to drop out of school at an early age to contribute to the household income, and his lack of formal education due to poverty, despite his immense yearning to learn, is a prevalent theme in many depictions of his life. In 1964, Jeon ran away from home and went to Seoul where he worked a variety of jobs—from street peddling to shoe polishing—to eke out a living. He was then employed by the Seoul Pyeonghwa Market as an assistant, thanks to the sewing skills he learned from his father, and later progressed to become a tailor.

It was his time working in the Pyeonghwa Market that was formative to his beliefs and values. As a witness to the atrocious working conditions in the factories and sweatshops there, Jeon was especially horrified by the treatment of female workers, who were often children as young as 12, and this spurred him to learn about labor laws of that time. Quickly realizing the numerous labor violations these sweatshops committed, Jeon founded the Fool’s Association (Babohoe 바보회) in 1969: the first organization dedicated to the rights of laborers in Pyeonghwa Market. He helped inform workers of their rights and the cruelties of their working conditions, later conducting a survey to compile a report on the working conditions in the factories. But Jeon and activists like him were largely ignored and repressed by the authoritarian government of Park Chung-Hee . It was precisely this apathy and resistance of the government and general society that prompted Jeon to take the extreme measure of self-immolation to call attention to these issues.

Though the gravity and importance of his actions and advocacy cannot be denied, the ways in which his legacy and story have been marshalled throughout history, as well as his own position within labor movements both past and present, are complicated. His death subsequently inspired a wave of workers to carry on his struggle. There were protests immediately after his death such as the Gwangju Settlers’ Riot in 1971, and multiple labor unions were later created that eventually made gains in securing workers’ rights. The spirit of his struggle also helped to unite many formerly divided groups (such as university students, the media, factory workers, religious officials, etc.) that made up an essential current of the larger democratization movement that continued into the following decades.

One thing which points to a more troubling aspect of his legacy is the way Jeon Tae-il is frequently referred to as “열사” (烈士), or “patriotic martyr.” This honorary title has been bestowed to numerous, quasi-legendary figures in Korea’s history, including Yu Gwan-sun, the young female independence activist during the Japanese colonial period who was imprisoned and tortured to death for her participation in the March 1st Movement. Without denying the value of Jeon or Yu’s actions, the contemporary celebrations of these figures as “patriots” or “martyrs for the nation” conceal the fact that it was often the very state and its apparatuses that they were fighting against. It is no coincidence, for instance, that fictional representations of Yu Gwan-sun as a chaste, innocent young girl who sacrificed herself out of a love for her country proliferated during the Park Chung-Hee regime, which sought to reinforce gender norms that designated women’s appropriate place as in the home. In other words, by inscribing their actions within the parameters of the nation-state, their more radical ideas and the movements they inspired are diluted and selectively summoned to reinforce hegemonic narratives that serve to consolidate the state and its power. These figures dared to imagine a new world, to dream otherwise and reach for new horizons of the possible. In limiting our commemorations of these figures as martyrs of the state so, too, do we limit our own political imaginations of change.

We would do well to remember in our present moment that Jeon’s sacrifices and death were not for the nation-state, but for the people—and more specifically, for the most marginalized people in society. He was spurred to action after seeing the atrocious working conditions of not just factory workers, but young female factory workers specifically, who had all but been forgotten by society. Jeon also sought to build larger coalitions that transcended social class distinctions, fighting for a collective movement. In that sense, his elevation to the status of a lone martyr is paradoxical and points to the dangers of lionizing individuals—of making societal change contingent upon a single, hero-like figure and thereby ignoring the work of coalition-building and the countless nameless individuals who comprise a movement.

Though Jeon’s actions were born out of a particular historical moment, in a particular place, his legacy still holds at least two lessons for us today. First, that nationalism has no place in the labor movement which, in the context of South Korea, has long been imbued with a masculinity that has ignored the plights of women, migrant workers, and anyone who may be deemed an “Other.” But just as Jeon Tae-il was inspired to action by the female textile workers, we are also compelled to realize that any rights or freedoms gained by the oppression of others do not constitute liberation. Second, that the celebration of individual figures, rather than collective actions, is often contingent upon the erasure of countless others. Why, for instance, is the name of Jeon Tae-il so widely known but not the names of the female workers of Dong Il Textile and Y. H Trading Company, who attempted to create their own union in the 1970s to address gender-specific labor issues? How many of us can easily mourn Jeon Tae-il and his death fifty years ago, but not the deaths of the migrant workers today who are reduced to a statistic and country of origin in the news? Though it may be far messier and more difficult to pay attention to the multitude of people whose experiences may never completely align with our own comprehensions of the world, interrogating the complicated intersections between gender, race, and class rings truer to Jeon’s legacy, and it is our duty to carry it on.

Translator’s note: Most representations of Jeon (both fictional and non-fictional) depict his deep love of learning. His collection of writings, ranging from essays, diary entries, to outlines of novels he one day hoped to write, also underscores this zeal to learn, a rare and genuine intellectual curiosity that is all the more heartbreaking for reminding us what could have been. In a way, Jeon’s very life embodies the tragedies and cruelties of capitalism, where poverty permanently shuts so many doors.

In the original Korean text, we can see Jeon’s numerous spelling and grammar mistakes (with occasional notes by editors to indicate the correct orthography) which are inevitably lost in the English translation. Yet these writings, intimate in every sense of the word, demonstrate an innate sense of rhythm, imagery, and poetry. Even as he describes the desperate conditions of society, his words reveal a deep love and hope for his fellow human beings, reminding us of the right to a dignified life for all people. Though spelling and grammar errors are not visible in the English below, in my translation I have tried to remain true to the authentic, raw, and poetic quality of Jeon’s writing.

All errors are completely my own. Many thanks to the Jeon Tae-il Memorial Foundation who gave their permission for this text to appear here.

The following excerpts are from Jeon Tae-il’s collected writings, Do not let my death be in vain (Nae jugeumeul heotdoei malla), edited by the Jeon Tae-il Memorial Foundation (Jeon taeil ginyeom saeopoe) and published by Dolbegae Press in 1988.

*

“The Struggles of a Youth Rebelling Against the Older Generation’s Perspectives on the Economy”

Editor’s Note [in the original]: This text is an outline for a planned novel, written by Jeon Tae-il around April 1970 [the year of his death]. Here, Jeon describes how he first came to participate in the labor movement, and the experiences he underwent to reach the present day. The first part describes his actions in the labor movement, and the last part, in tracing his thoughts about what it means to die for a struggle, demonstrates that he had already sensed the inevitability of his own death.

Part I

When: March 16, 1969 – present

Where: The city of Seoul

Subject: Freedom and self-indulgence. The present society of the current generation and the older generation’s perspectives on the economy. The struggles of a youth rebelling against the older generation’s perspectives on the economy which are currently shaping reality.

J (Main Character): A 23 year old garment cutter who works in a factory

B: A frail young girl in her twenties who works on the sewing machines in a textile factory and greatly influences J’s thinking.

Plot Outline

1. Opens with the noisy sounds of a factory in Jungbu Market and the pure humanity of B who is being abused.

2. J’s decision and resolve after his shock at seeing how horribly B is treated.

3. J’s great pain resulting from the factory environment, overwork, and work-related illness and the reason he is unable to go to work.

4. The painful ordeals at the cramped clothing alteration shop in Guro-dong and the death of J’s father.

5. The difference of opinions between J, who organizes the Fool’s Association [Babohoe] and the other garment cutters who are his friends.

6. J’s feelings and state of mind after failing to hold another general meeting after the association’s inauguration ceremony and how J prints surveys with the pittance he earned for 5 days working at a pants manufacturer.

7. J’s family situation and his family members’ personalities.

8. J’s bewilderment and disconcertment after reflecting on the true conditions of present society and what ordinary people seem to think.

a. Though the survey earlier distributed represents the will and intentions of the factory workers, the factory owners violate the human rights of 30,000 workers through pressure and coercion.

9. The apathetic stance of the labor supervisors in City Hall and J’s emotions.

10. J’s disappointment, after having believed in society, and his subsequent disillusionment.

11. The deceitful personality of the Hanmi factory’s owner and the disappointment of 18 year old J, who confronted society for the first time, as well as J’s condition after nearly becoming a victim of the older generation’s poisonous greed.

12. The Hyeonsip factory owner’s inhumane beliefs on the economy, the factory workers and J’s pent-up anger and frustration in seeing the way factory owners abuse their power.

13. Wandering. Fantasizing about criminals and how to earn money.

14. J’s feeling of unendurable suffocation from being trapped in this kind of societal environment, and J’s wanderings as he instinctively tries to escape.

15. The important address J made to the members of the Fool’s Association at its inauguration and J’s feeling of disappointment and guilt to the factory workers in failing to resolve this problem. J’s pitiful struggling in order to fulfill his sense of responsibility after only obtaining disappointing results with regards to this problem.

16. Traveling to Daegu, the hometown of J’s body and soul, where his most beautiful memories are. Having decided that he will tread the sorrowful path of death, he gathers his old friends for a party that will double as a farewell, making for a tearful Christmas Eve.

17. J boasts about himself in front of his old school mates. J talks himself up, exaggerating to the extreme, not believing that such things would ever come to pass. But with his talk, he himself starts to feel as if it could happen before long, as he exaggerates to his old school mates and explains a future role for himself that is totally unrealistic. He tells them about building an educational institute for factory technician workers that will double as a recreational facility, and addresses the issue of technician workers’ social status and developing the depth of character required of those who will be the mothers of Korea’s future. He talks about the sources and methods of fundraising the money needed to prepare all these various conditions for technician workers. For a brief moment, everyone present is overwhelmed with emotion. J himself momentarily thinks that he will really turn out this way, and after shuddering at the social environment that he alone senses, he explains what his position will be in a few months’ time according to his original plans. Exaggerating terribly.

18. J returns to Seoul and viscerally feels society’s reaction, and makes his last arrangements.

19. J’s friends wait for him in Daegu. They promise to meet again on April 19. All that is there is a single sheet of paper, fluttering: J’s last will and testament.

Part II

My dear friends, I hope you read this.

My dear friends, it is I, in my entirety

All of me, even the parts I do not know myself.

I have a favor to ask. Please do not forget me, as I am in this moment.

This is my wish. That you cherish me in the library of your precious memories.

Even if thunder and lightning burn this insignificant body, even if the sky comes crashing down on me, cherished in your precious memories, I will not be afraid. And should fear decide to remain, I will still throw my own self away. I am a part of you all, who know me. I am sorry for participating only invisibly in this gathering of yours. Please forgive me.

Save me a seat in the middle of the table. A seat between Wonseop and Jaecheol would be even better.

If you have made a seat for me, please listen to my words. Me, a part of you, all who know me. Working so hard to gather the strength to push this boulder, I find I am no longer able and I leave this boulder that must continue to be pushed to you all, who are a part of me. I must briefly go now. To briefly rest. In refusing to give in to the oppressive arms and forces of the authorities in the present, in some future world, I will continue pushing this boulder to its final destination, though I have been unable to do so in my current life. Even if I am banished from that future world, I will carry on.

I will continue pushing, but if only I could help. I hope we make it.

*

The wind is fierce. The cosmos flowers struggle to bend their slender backs. The blooms of the lanky sunflowers are heavy, begging the wind as they proudly stoop from their heights: “Please, Sir Wind, contain your fury and settle down.” The rose moss blossoms are amused at the sight of the bending and begging sunflowers. Underneath the sunflowers, the cockscombs struggle to contain their laughter but finally burst out laughing in yellow. The cosmos, worried their backs will break, lean against the wire fence. As if it had been waiting all along for this, the wire fence closely hugs those slender stems. The faces of the cosmos are pale from their shame, from their strained backs. Their throats hoarse and pained from pleading, the gangly sunflowers weep yellow tears with their petals fluttering in the wind.

Lost in his thoughts, JL sits on the floor and stares at the flower fields. Though his gaze never leaves the flowers in front of the wire fence, his thoughts are far away at Jungbu Market, ruminating on the events that transpired yesterday at work. The state of Garment Worker #5 as she expressed her faint hopes to him:

“Excuse me, sir, but could you see if there’s a place where it’d be possible for us to rest on Sundays?”

“Let’s see. Apart from something like a bonded factory, there aren’t very many places like that. Maybe if people who believed in hope and happiness were the ones that created factories, but I haven’t seen many such places. Either way, I’ll try my best to find out as quickly as possible.”

Upon this insincere answer, Garment Worker #5 naively thanked him in the only way she knew how. Though he said that he would find a place right away, there was no such place where one could hope for.

*

The wind is fierce. The cosmos flowers struggle to bend their delicate backs. The blooms of the lanky sunflowers are heavy, begging the wind as they proudly stoop from their heights: “Please, Sir Wind, contain your fury and settle down.” The rose moss blossoms are amused and brightly smile at the sight of the bending and begging sunflowers. Underneath the sunflowers, the cockscombs’ cheeks turn red from struggling to contain their laughter and they lower their faces. The cosmos, worried their backs will break, lean against the wire fence. As if it had been waiting for eternity, the wire fence closely hugs those slender stems. Worried that someone might see them, the faces of the cosmos are pale from their shame, from their strained backs. Their throats hoarse and pained from pleading, the gangly sunflowers weep yellow tears with their petals fluttering in the wind.

*

Teacher, a reality like this exists. One father has thirty children. In that house, they make and sell clothes to earn their living, but a few years later, the household’s conditions improve and they become rich. But the father continues to order the children around the same way. No, the father treats them even worse than before. And the father lives a comfortable and easy life while exploiting the children. The father spends 200 won on a single meal, while giving the children 50 won to cover all their meals for a day. This is behavior no true human being could ever commit. Even if the father is the leader and the children are the weak, these children are also human beings. The children start to resist. They demand that their father give them time to rest. They demand more bread, enough bread so that they can finally feel full. But instead of giving them bread, he forces them to work 16 hours a day. Young children cannot do hard physical labor for 16 hours a day. Even if they are young and uneducated, they are also people—they are also human beings. They are God’s creations that from the moment of their birth, know how to think, how to love good things, how to laugh at happy things: they are human. Though they are all the same human beings, how is it that the poor become the slaves of the rich? Why is it that the poor do not have the right to observe Sabbath, a day that the Lord himself chose?

In religion, all human beings are equal.

In the law, all human beings are equal.

Why must the pure and innocent children become the fuel of the dirty and stained rich? Is this the reality of society? Is this the fundamental rule of the poor and the rich? Human life is precious. The life of the weak is just as precious as the life of the rich. All living beings are precious. The desire to not want to die is a natural instinct of all living creatures. Teacher, there are people here who do not understand this instinct. There are those who wait for death, wanting to avoid pain. And they are dying. Not microbes, nor beasts, there are people like this. In the environment of the rich, these people are denied and the structure known as society is using the weak as its fertilizer. As fuel to make the rich even richer.

Teacher, these human beings yearn for bread and time—for freedom. It is not enough that only one of these needs is satisfied. No matter how much bread there is, no matter how much freedom there is, if the weak cannot also participate, humankind will always have grievances. We demand adequate bread and rest. Teacher, please help us convey our message to those that employ us. We yearn, for enough bread and enough rest. Not for self-indulgence, but for freedom. Not even for pleasure or bliss, but for physical rest. Not for a sumptuous feast, but for enough stale bread and water to sustain the body.

“I Must Die”

Editor’s Note [in the original]: This text, a kind of written resolution, was written by Jeon in his diary on August 9, 1970, approximately four months after he arrived at Samgaksan. At the end of April of that same year, Jeon had directly grappled with the problem of being involved in a struggle where death was the only possible remaining option, and started working at a construction site for the Samgaksan church as a laborer in order to never waver from his decision again. By this time, Jeon had already assumed that he would have to die and had even written a last will and testament. Thus, on August 9th, Jeon declared his final resolution to die for the struggle. A portion of this text is missing from Jeon’s diary and is not included here.

How much time have I spent hesitating and agonizing after initially making my decision? At this moment, I am almost perfectly determined.

I must die.

I absolutely must die.

To return to the sides of my poor comrades, to the hometown of my heart, to those young innocents of Pyeonghwa Market who form the entirety of my ideals, I, who have vowed to lay down my life in those endless stretches of time and daydreams, must die to join those fragile beings that need my protection and care.

I must throw myself away, I must destroy myself. Just wait and hold on a little longer. So that I will never leave your sides, I devote the entirety of myself, weak as I am, to you. It is all of you that are the hometown of my heart.

[…]

Today is Saturday. The second Saturday of August. The day I have resolved my heart. In this moment, when innocent lives are withering—O Heavenly Father, please grant me your mercy and compassion so that I may become a single drop of dew.

— August 9, 1970.