Heung | 흥 Coalition

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

︎ Instagram

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

A Diaspora of Dignity: Remapping Black-Korean Solidarities and Histories of Resistance in the Korean Diaspora

April 5, 2021

By: Young Oh Jung

Edited By: Rachel Min Park

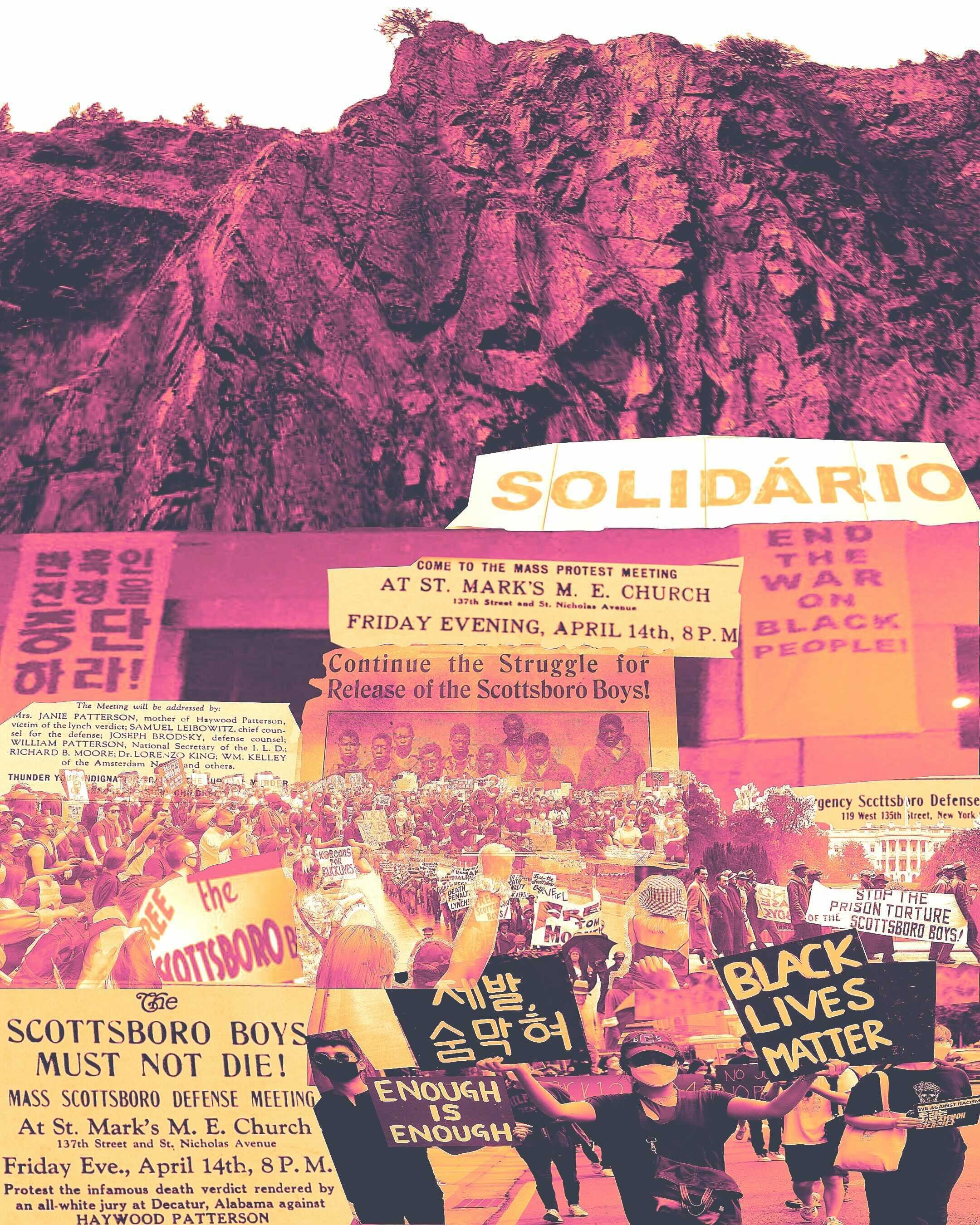

Collage by Grayson Lee

A Radical Reimagining

In January 1932, Kim Ho Chul, a Korean immigrant student, was imprisoned in Cooks County Jail of Chicago for participating in the campaign to free eight Black teenagers sentenced to death by electric chair after being wrongfully accused of raping two white women in Alabama on March 25th, 1931. This incident was a set of landmark legal cases known as the Scottsboro Boys case, one of the countless examples of racial injustice and a flawed judicial system which have continuously inflicted both physical and psychological violence on African Americans throughout American history. Kim’s arrest subsequently led to his deportation as he was ordered to leave the country within a month after his release. Kim’s act of radical solidarity at the cost of his imprisonment and deportation can be further seen through a poem he wrote while imprisoned in Cooks County Jail, “To the Eight Black Children,” which was published in the diasporic Korean newspaper Sinhan minbo on January 28, 1932.

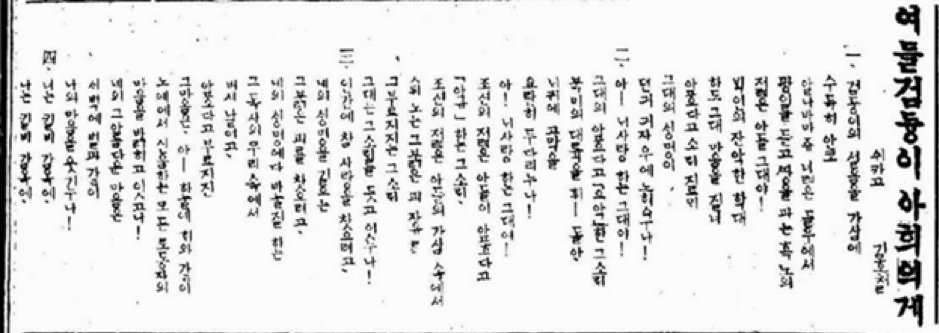

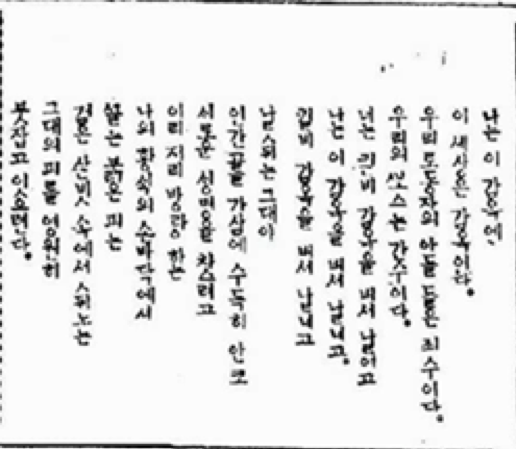

Kim Ho Chul, “To the Eight Black Children,” originally published in Sinhan minbo, January 28, 1932.

Clutching the Black child’s sorrow

to my chest

It is the young child

of the Black laborers grasping their hoes and digging the earth

on the wide Alabama fields!

Because you screamed in pain

from the white man’s cruelty,

because it so pierced your heart

they placed your life

on the electric chair!

You, my beloved!

The sounds of your pained gasps

whirled through the continent of North America

to loudly beat against

my eardrums!

You, my beloved!

The pained groans

of Joseon’s young sons,

that sound clamoring for freedom,

that crimson blood flowing

in the hearts of Joseon’s young sons—

Are you listening to these cries?

Searching for a true love of humanity,

searching for that crimson blood

that cultivates your life

To escape

from the flocks of venomous snakes

that encircle your life

That heart

screaming in pain with the sky’s sea

You reveal the hearts

of all laborers groaning under slavery!

Your beautiful heart

like the dawn’s stars

makes my own heart smile!

You, in Kilby and I, in this jail

This world is a prison.

We, the sons of workers, are prisoners,

our boss the prison guards.

You, trying to escape the prison of Killby[1]

while I try to escape this one.

As you frantically struggle

trying to escape Kilby,

clutching in your heart

the suffering of humanity,

that red blood boiling

in my yellow palms.

As I wander here and there,

trying to find a new life,

I will forever cling on to your blood

that playfully and freely flows

underneath your black skin.

to my chest

It is the young child

of the Black laborers grasping their hoes and digging the earth

on the wide Alabama fields!

Because you screamed in pain

from the white man’s cruelty,

because it so pierced your heart

they placed your life

on the electric chair!

You, my beloved!

The sounds of your pained gasps

whirled through the continent of North America

to loudly beat against

my eardrums!

You, my beloved!

The pained groans

of Joseon’s young sons,

that sound clamoring for freedom,

that crimson blood flowing

in the hearts of Joseon’s young sons—

Are you listening to these cries?

Searching for a true love of humanity,

searching for that crimson blood

that cultivates your life

To escape

from the flocks of venomous snakes

that encircle your life

That heart

screaming in pain with the sky’s sea

You reveal the hearts

of all laborers groaning under slavery!

Your beautiful heart

like the dawn’s stars

makes my own heart smile!

You, in Kilby and I, in this jail

This world is a prison.

We, the sons of workers, are prisoners,

our boss the prison guards.

You, trying to escape the prison of Killby[1]

while I try to escape this one.

As you frantically struggle

trying to escape Kilby,

clutching in your heart

the suffering of humanity,

that red blood boiling

in my yellow palms.

As I wander here and there,

trying to find a new life,

I will forever cling on to your blood

that playfully and freely flows

underneath your black skin.

검둥이의 설움을 가슴에

수득히 안고

앨라버마주 넓은 들 위에서

괭이를 들고 땅을 파는 흑노 (黑奴)의

젊은 아들 그대야!

백인의 잔악한 학대

하도 그대 마음을 질러

아프다고 소리 지르매

그대의 생명이

전기의자 위에 놓였구나!

아! 내 사랑하는 그대야!

그대의 아프다고 ‘으악’한 그 소리

북미의 대륙을 휘 - 돌아

내 귀의 고막을

요란히 두드리누나!

아! 내 사랑하는 그대여!

조선의 젊은 아들이 아프다고

“아규”하는 그 소리

조선의 젊은 아들의 가슴 속에서

뛰노는 그 붉은 피 자유를

부르짖는 그 소리

그대는 그대는 그 소리를 듣고 있느냐.

인간의 참 사랑을 찾으려고

너의 생명을 기르는

그 붉은 피를 찾으려고

너의 생명에다 바느질하는

그 독사의 무리 속에서

벗어나려고

아프다고 부르짖은

그 마음은, 아 - 하늘의 해와 같이

노예에서 신음하는 모든 노동자의

마음을 밝히고 있구나!

너의 아름다운 마음은

새벽의 별과 같이

나의 마음을 웃기누나!

너는 킬비감옥에

나는 이 감옥에

이 세상은 감옥이다.

우리 노동자의 아들들은 죄수이다.

우리의 보스는 간수이다.

너는 킬비감옥을 벗어나려고

나는 이 감옥을 벗어나려고

킬비감옥을 벗어나려고

날뛰는 그대야

인간고(人間苦)를 가슴에 수득히 안고

새로운 생명을 찾으려고

이리저리 방랑하는

나의 황색의 손바닥에서

끓는 붉은 피는

검은 살빛 속에서 뛰노는

그대의 피를 영원히 붙잡고 있으련다.

수득히 안고

앨라버마주 넓은 들 위에서

괭이를 들고 땅을 파는 흑노 (黑奴)의

젊은 아들 그대야!

백인의 잔악한 학대

하도 그대 마음을 질러

아프다고 소리 지르매

그대의 생명이

전기의자 위에 놓였구나!

아! 내 사랑하는 그대야!

그대의 아프다고 ‘으악’한 그 소리

북미의 대륙을 휘 - 돌아

내 귀의 고막을

요란히 두드리누나!

아! 내 사랑하는 그대여!

조선의 젊은 아들이 아프다고

“아규”하는 그 소리

조선의 젊은 아들의 가슴 속에서

뛰노는 그 붉은 피 자유를

부르짖는 그 소리

그대는 그대는 그 소리를 듣고 있느냐.

인간의 참 사랑을 찾으려고

너의 생명을 기르는

그 붉은 피를 찾으려고

너의 생명에다 바느질하는

그 독사의 무리 속에서

벗어나려고

아프다고 부르짖은

그 마음은, 아 - 하늘의 해와 같이

노예에서 신음하는 모든 노동자의

마음을 밝히고 있구나!

너의 아름다운 마음은

새벽의 별과 같이

나의 마음을 웃기누나!

너는 킬비감옥에

나는 이 감옥에

이 세상은 감옥이다.

우리 노동자의 아들들은 죄수이다.

우리의 보스는 간수이다.

너는 킬비감옥을 벗어나려고

나는 이 감옥을 벗어나려고

킬비감옥을 벗어나려고

날뛰는 그대야

인간고(人間苦)를 가슴에 수득히 안고

새로운 생명을 찾으려고

이리저리 방랑하는

나의 황색의 손바닥에서

끓는 붉은 피는

검은 살빛 속에서 뛰노는

그대의 피를 영원히 붙잡고 있으련다.

I ran into this poem during the first year of my doctorate program in History, while working on a research paper on the history of Korean American militarism during the early 1900s. I was initially blown away by what it entailed and how important and meaningful this is to the Korean diaspora given the ever-present narratives based on the deadly mixture of ethnonationalism and permissible whiteness through the construction of the model minority myth and assimilatory whiteness. All of these ideals were antithetical to the cultivation of solidarities. I sat on it for a very long time, mostly because I had no idea how to tell Kim’s story from the training I received in graduate school as a historian and an archivist. No, I knew how, but I had a gut feeling that something was very wrong with using my academic training to do so.

History taught me to read, write, and teach more about division than solidarities because of what was available as “evidence,” as if documents solely defined who we are. The sanctity of empirical data and sources could never fully explore the intimate histories of our communities and the practice of community knowledge dismissed as ahistorical, compromised, unreliable, too personal, and too emotional. The institutionally-funded knowledge production of history traditionally does not accept concurrent histories of complex personhood and contradictions filled with stories of conflict and solidarities, of community building and strife, that is non-linear and nonconforming.

“The sanctity of empirical data and sources could never fully explore the intimate histories of our communities and the practice of community knowledge dismissed as ahistorical, compromised, unreliable, too personal, and too emotional. The institutionally-funded knowledge production of history traditionally does not accept concurrent histories of complex personhood and contradictions filled with stories of conflict and solidarities, of community building and strife, that is non-linear and nonconforming.”

To put it bluntly, I didn’t want to fuck it up. I didn’t want to fuck it up with traditional archival methods that normalize extractive knowledge production simply to glorify the discovery of “unchartered” and “unexplored” scholarship. I didn’t want to fuck it up with the tendency of the historian to view sources as currency used to purchase a form of linear storytelling devoid of experience, kinship, and possibilities.

For the historian, proclaiming that nothing can be done with what is absent from the archive serves as justification to continue the search for sources that can fill the gaps of a linear narrative because “you can’t just make shit up.” If I told this story the way I was trained as a historian, I knew I would obsess over distinguishing between “facts” and “objectivity” with “speculations” and “guesstimations.” As much as I can attempt to push the boundaries of historical knowledge, I knew I would be limited by the unspoken sacred rules of the discipline that would only permit me to justify, sell, and claim ownership of a historical narrative that was not mine to take. I keep going back to what Chang-rae Lee told the audience in a book talk about what it means to be a writer. "As a writer, it is about language and emotion. Not new stories or brilliant ideas. It's about fearlessness, about letting yourself go and trying to be free."[2] A radical reimagining of the archive and historical methods was needed to locate the possibilities of solidarities amid the entanglements of the transnational and the diaspora. This piece is an ongoing process of decolonizing myself from the rooted systematic disciplining of academia and the field of history, trying to figure out what it means to practice and write on solidarities from my own positionality as a historian of the Korean diaspora.

A Forgotten, Layered History

Kim Ho Chul immigrated to the U.S. in 1927 to pursue his studies, following his father who was one of the first Korean students to study abroad in the U.S. Despite his family’s difficult circumstances, Kim’s father encouraged him to seek new experiences and education overseas and prioritized his education in Korea. Kim was able to leave for the U.S. with help from a family acquaintance, Mr. Baek, who had already sponsored Kim’s brother to study abroad in Melbourne in 1921.[3] Kim was able to follow Mr. Baek to the U.S. where he began his business in the rubber trade. Kim’s background and experience differed from many other renowned early Korean immigrants who started off as students and activists in the U.S. These diasporic Koreans were mainly part of “the (Christian) liberal-bourgeoise subjectivity that emerged in Korea at the turn of the century” of upper class yangban* status who gained favor and connections with American missionaries in the early 1900s.[4] In contrast, Kim arrived at San Francisco Harbor with four dollars in his pocket and worked in various service industry jobs at hotels and restaurants while overseas.[5] While working in the Virginia Hotel before he moved to Chicago to start school, Kim stated that he experienced first-hand the “exploitation at the hands of the Americans'' and sought to connect with anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist activists while studying at Lewis College.[6]

Kim’s upbringing in Korea very much influenced his activities overseas. Even though his father was one of the first Korean international students in the U.S., he incurred much debt after his studies working as a pollock, ginseng, and salt trader in Japan, Russia, and Hawai‘i.[7] Kim worked various jobs such as selling crab and lumber to survive and provide for his family, and remembers the shame and hunger they endured as an adolescent. For example, Kim remembers the debt collectors beating his father and taking his rice bowl away; being “treated like a dog” by his landlord who mocked him after tossing him leftovers; and the flowing tears of his mother watching him devour the food.[8] At an early age, Kim also participated in the March 1st Movement of 1919, shouting “Chosun doklip mansei! (Long Live Korean Independence!)” with his classmates in front of a police station.[9] Kim was severely beaten by policemen and reprimanded by his teachers who mocked his actions and dismissed them as foolish.[10]

As a student in Lewis College, he was very much active in the Korean American international student community as a member of the Korean American Social Science Research Group and a frequent contributor to the Sinhan minbo. Kim was also an active participant of revolutionary politics that concerned both his homeland and domestic politics and social issues within the U.S such as worker’s rights and racial inequality. This is revealed by his membership in the Anti-Colonial Alliance that sought to overthrow Japanese colonial power in the Korean peninsula and the American Revolutionary Writers League (ARWL).[11] It was in ARWL, which he joined in 1929, where he began to focus on the plight of African Americans from slavery to reconstruction.

While Kim’s arrest was due to his participation in the movement to overturn the death sentence of the wrongly imprisoned teenagers, it is unclear if his affiliation with the ARWL or the Anti-Colonial Alliance led to his deportation order. This is certainly a possibility given that ARWL was supported by the American Communist Party and the Anti-Colonial Alliance was part of the larger socialist internationalist movement calling for anti-imperialism. Historian Pang Sŏnju suspects that other Korean Americans might have notified immigration officials as his public proclamation of his communist ideals in the pages of Sinhan minbo might have alarmed the majority of Korean Americans who were very much pro-U.S. and anticommunist.[12] Kim was imprisoned for around 4 months and released on May 10th, 1932 and was originally due to be extradited across the Pacific to Japanese authorities for his part in the Korean liberation movement overseas.[13] However, his associates in revolutionary organizations lobbied the courts to allow him 30 days to leave the American borders and helped him relocate to Berlin.[14] Kim stayed in Berlin during July 1932, working with the Red Aid movement before Hitler’s purge of communists after the Reichstag fire.[15] Kim then moved to Moscow to work with the International Red Aid for 6 months before he returning home to Hungnam where he was arrested and sentenced to 5 years in prison for his involvement in organizing a Red Aid group.[16]

Reimagining Histories of Solidarities

“To the Eight Black Children” is a call for solidarity empathetically connecting the experiences of African Americans’ racial injustice with the oppressive subjugation of Japanese imperialism endured by Koreans back in his homeland. Kim’s story goes beyond what archives justify as political fervor and conviction for socialist internationalism through his transnational involvement and membership with various political organizations. What exists in the gaps of this history, which cannot be solely discovered in the traditional archives, is how he was able to deeply engage with the indignity and violence suffered by the teenagers on death row and practice what can be considered the origins of Black-Korean solidarities. By reading the language used in the poem alongside his background and family history, we can grasp how Kim was able to position his diasporic identity and his anti-colonial activism with the struggle against racial inequality in the U.S.

In the poem, Kim acknowledges the struggles of the Black working class of the South and the deeply rooted racism that pervades society as he attempts to intersect his own struggles and pain, as well as that of his homeland. For Kim, the “sound of pain” echoes beyond the American mainland towards the Korean peninsula where “Joseon’s young sons” are “clamoring for freedom.” For Kim, their suffering leads to a mutual struggle that serves as a powerful impetus to cultivate solidarities beyond ethnic divides and political allegiances.

While Kim’s knowledge of the African American experience and racial inequality supposedly stemmed from what he was able to learn as a member of the ARWL, reading the life stories of the teenage boys and Kim in conjunction reveals more intimate connections between the experiences of struggling against larger forces such as colonialism, capitalism, and racial injustice. The blatant injustice induced by the “white man’s cruelty” that Kim writes in his poem is evident through what the boys experienced before and after their arrest. The eight teenagers were arrested when a fight broke out with a group of white men on a train and were subsequently accused of rape. After their arrest, they were threatened by lynch mobs, beaten, and tortured by police and prison guards to testify against each other. One of the boys, Ozie Powell, was also shot in the head after a scuffle with a police officer, resulting in permanent brain damage. Most of the boys were on the train to look for work or traveling to and from their jobs working as farmers, loggers, busboys, and grocery baggers, jobs similar to those Kim held to survive in Korea and as a student overseas. Though what Kim endured pales in comparison to what the eight teenagers endured, Kim still attempts to relationally connect and engage the inequalities and injustice suffered by the boys as best as he can with his own struggles both as part of the working class and the colonized masses.

The injustice would also remind him of the March 1st Movement, which he was a part of in Hamhung, when he was beaten and ridiculed by authorities. Along with Kim, two million Korean men, women, and children marched across the nation proclaiming independence from the Japanese Empire that colonized and militaristically occupied the Korean peninsula since 1910. Over the course of more than 1,500 demonstrations, thousands were gunned down and executed or arrested by Japanese military and police. The protests continued for over a month until they were crushed by force, paving the way for future atrocities committed by the colonial authorities.

For Kim, suffering under the oppressive forces of Japanese colonialism in the Korean peninsula and white supremacy in the American South was a mutual struggle for justice, a search for “a true love of humanity.” Writing under the circumstances of deportation, possibly to Japanese authorities, Kim was able to hold on to hope by acknowledging the boys’ fight for survival and justice amidst the terror and violence inflicted upon them. It was their struggle that made Kim’s “own heart smile.” Kim ends the poem with a beautiful proclamation of solidarities that has a historic significance through the mention of his and the Scottsboro Boys’ blood. With the “one-drop rule” long utilized as a social and legal basis of racial classification and continued oppression in the U. S., blood has also been the principle of maintaining the centuries-old caste system throughout Korean history that deeply impacted subsequent contemporary class structures in Korean society. The collective fight for justice across the Pacific for Kim superseded ethnic and blood ties that have been normalized as the most fundamental grounds for hierarchical oppression.

Writing Diaspora’s History

Kim’s ability to find and claim solidarities in a mutual struggle and of blood has its roots in the complex multiplicity of diasporic identity. In exploring such a topic, I found much refuge and encouragement in the intellectual space held by scholars of the African diaspora who have influenced and inspired me greatly. In her attempt to retrace the routes of the Atlantic Slave Trade in Lose Your Mother (2007), Saidiya Hartman recounts her journey as a process of contemplating the difficult and complicated history of loss, despair, and difference in the African diaspora. When Hartman learned of the resistance against slavery in Gwolu, she began to link this history with current struggles of the African diaspora in the United States and beyond. For Hartman, the collective resistance against slavery in Gwolu and the struggle against racial oppression represents the fight against “slavery in all of its myriad forms.”[17] This fight thus connected Black communities through their histories of resilience and resistance as Hartman states, “The bridge between the people of Gwolu and me wasn’t what we had suffered or what we had endured but the aspirations that fueled flight and the yearning for freedom.”[18] For Hartman, engaging with a past filled with gaps and embracing the untraceable guided her towards possibilities of transnational solidarity as she states, “My future was entangled with it (Africa), just as it was entangled with every other place on the globe where people were struggling to live and hoping to thrive.”[19]

Kim was someone who “wander[s] here and there / trying to find a new life.” For the transpacific Korean diaspora during and after Kim’s time, a “new life” pertains to a new beginning, a new country, home, identity, culture. They searched for something “better” than what they had lost with Japanese colonization, the unended Korean War and the subsequent national division, the decades long militarized authoritarianism; all were part of the continual perpetuation of both the visible and invisible violences of Imperial occupation and US Militarism in the Korean peninsula. And for this “better new life,” the diaspora shapes their identities fluidly, choosing what to accept and reject from their old and new cultures and selves. The “better new life” Kim chose was that of collective resistance against relational injustice made possible by his ability to converge his own struggle for dignity empathetically with others through his diasporic identity. While Kim faced further exile and persecution, his belief in the mutual struggle for true justice breathed life into his continued journey.

Kim’s story reveals how diasporic identity continuously develops as a process that expands beyond its conventional understanding as dispersion of an ethnonational collective, often utilized to explore ethnic homogeneity and engagement of homeland politics. Historians Pang Sŏnju and Suzy Kim, who have written on Kim, identify him as a leftist Korean independence activist overseas, and a North Korean who utilized the assemblage of his identities in Korea and overseas to formulate a résumé, pointing to his experience overseas as a socialist international. These two identities discovered in a pile of documents in state archives are definitely part of Kim’s story, but are limited by the rules of the archives and historical methodology to comprehend what lies beyond the legible and documented. By understanding the multiplicity of diasporic identity formation as a continual process, we can locate within the historical gaps the shifts and contradictions of diasporic identities that defines its in-betweenness, as well as stories of racial solidarities engaged by Kim and others in the Korean diaspora that continue to this day. Diasporic identities are “never completed, never finished” and always “in process.”[20] According to Stuart Hall, this process is a task of “recognizing that all of us are composed of multiple social identities, not of one. That we are all complexly constructed through different categories, of different antagonisms, and these may have the effect of locating us socially in multiple positions of marginality and subordination, but positions which do not yet operate on us in exactly the same way.”[21]

Solidarities is a lifelong endeavor and process that takes a multiplicity of struggles. And again, much like the diaspora, solidarities is a process that is layered, complicated, flawed, and incomplete. This is evident in Kim Ho Chul’s story as well. Kim’s use of the terminology “gumdoongi” (검둥이) to refer to the “black children'' in the poem, a derogatory slang used towards other Koreans with darker skin and later towards black people, is very troubling and both contradicts and jeopardizes whatever solidarities that he was trying to establish. There are numerous ways to try and unpack and justify the use of the terminology from the history of colorism in East Asia, lack of cultural exposure to Black communities, and the innate consumption of anti-blackness as whiteness in their cultural assimilation. However, these excuses have been used far too often to justify the fallacies of our histories. Calls for dialogue and understanding from both the perpetrators and the complicit without accountability in the internalizing of whiteness have degraded the foundation of any form of solidarities.

Kim’s story also participates in the continued erasure of women as well as the perpetuation of patriarchal hierarchy and masculinist violence constant in the historical narratives of Korea and by extension, the Korean diaspora. The “painful groans” and the flowing “crimson blood” resulting from colonial oppression and the subsequent resistance belong solely to “Joseon’s young sons.” Even as he laments the tears and suffering of his mother, her anguish, along with those of the countless women who resisted Japanese occupation, are considered subsidiary to the persecution and defiance of Korean men as the leading actors of Korean independence.

Such issues have also plagued the available histories of the Korean diaspora that overlook the racialized and gendered hierarchies ever-present in the telling of our histories. The limitations of engagement and archives also justify without repercussion the privileging of male-centered histories and the universal establishment of an androcentric narrative within diasporic Korean history that normalizes the erasure of women. What historians perceive as a conventional and linear production of historical knowledge participates in this gendered (and racialized) violence that perpetuates the absence of women and limits the possibilities of alternatively imagining the diaspora. Drawing upon the long-established cultivation of the historian’s expertise thus inevitably renders the diasporic Korean history project incomplete.

Diaspora of Dignity

On June 6th 2020, activists and the masses gathered in Liberty Park at the heart of Koreatown in Los Angeles, California as part of the mass demonstrations across the nation and major cities around the world to protest the unending police violence and racial injustice that resulted in the death of George Floyd and countless others. As people gathered in a circle in the middle of the park, the drumming team of the Olokun Cultural Group led by Najite Agindotan began to perform. During the performance, the dundunaba percussionist signaled to a woman kneeling besides him with a buk to join in. In a beautiful moment of solidarity, the sounds of buk, janggu, and kkangari began to follow the beats of the dundunba and djembe. As the Korean American pungmul group danced and performed with the rhythmic soul of the African diaspora, the beats that filled the park were of two diasporas acknowledging and supporting each other through the music and dance that had persevered through our cultures and histories of survival and resistance.[22]

The ringing sound of solidarities both ignited and restored hope, especially in a city where various forms of solidarities between the two communities have been constantly obscured and erased for three decades by the narrative of racial strife presented by the media and the unhindering norms of whiteness. The reliance and acceptance of whiteness have been amplified and normalized as the only form of assimilation and survival for communities of color, including Korean Americans. And it is no question that Koreatown has been a contentious and racialized space of unity, division, and contradiction where violence based on anti-blackness and ethnic solidarities coincidently take place. However, the constant efforts by activists and community members to engage, teach, and learn beyond the knowledge of division allow us to look back at the obscured but treasurable stories of mutual struggle and to look forward.[23] I find solace in the hope that what Kim Ho Chul practiced in 1931 was not a solitary and arbitrary endeavor. Despite the seeds of division that are constantly sowed and certified as the official narrative of history, much like the diaspora, solidarities are also a continuous process of discovery and learning, of accountability and change. As we constantly remind ourselves who and what this fight is for, we find ourselves together in the communal struggle for justice and dignity.

“Despite the seeds of division that are constantly sowed and certified as the official narrative of history, much like the diaspora, solidarities are also a continuous process of discovery and learning, of accountability and change. As we constantly remind ourselves who and what this fight is for, we find ourselves together in the communal struggle for justice and dignity.”

Trying to find the right words to conclude, I am left with more questions and doubts about how to do justice to the complicated stories of diaspora and solidarities especially in the current turbulent moment of Anti-Asian violence, especially after the mass shooting in Atlanta where 8 people were killed, with 6 of them being Asian women and immigrant workers. Hollow and sudden calls for “solidarities” and “empowerment” are presented as the solution as another form of diversity initiative that inevitably leads to more policing and the perpetuation of structural violence. Words are thrown around on the surface without any effort that dangerously co-opts and misrepresents the years of community engagement that took place in our neighborhoods to combat these violences directly connected to imperialism and racial capitalism that Kim was convicted to struggle against.[24] Our safety is not guaranteed with the façade of representation currently bombarded through the media, just as the narrative of “race war” was presented in the early 90s.

I constantly think of what Cedric Robinson meant as he ended Black Marxism with the words, “But for now, we must be as one.” But at least at the forefront, it begins with a multitude of struggles. And given the multiplicity and complexities of different peoples and different histories and the preconditions of understanding necessary to practice solidarities, our ultimate goal to “be one” grows from the root of empathy and dignity. The gendered and racialized narratives of our histories reveal its flawed incompleteness and a dire necessity to reframe the established narratives of the Korean diaspora. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore states, “…making solidarity is something that’s made and remade and remade it never just is. I think of it in terms of radical dependency…so solidarity and this radical dependency that I keep thinking about and seeing everywhere is - about life, and living together. And living together in beautiful ways.”[25] We must acknowledge our contradictions and build from the openness of the diaspora in which we can cultivate our roots beyond the boundaries of the nation-state and prescribed notions of homeland-based nationalisms and identity formations. It is from this fluid and transitory state that we find the space to merge and process our stories of struggle in a collective search for justice and dignity. It is the diaspora of dignity in which we root our solidarities.

Notes

[1] Killby Prison, currently Killby Correctional Facilities, was a Prison in Alabama specifically used during the 1920s and 1930s to execute prisoners by electric chair, a fate that the Scottsboro Boys faced. Some of the boys were placed in cells near the electric chair and were able to hear the screams during executions.

[2] This was a book talk in Seoul for On Such a Full Sea (2014) in May 2014.

[3] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong [Independent activism of Korean Americans], (Hallim Taehakkyo Asia munhwa yŏn'guso, 1989) 333-334.

[4] Henry Em, The Great Enterprise: Sovereignty and Historiography in Modern Korea, (Durham: Duke University Press) 75. Yangban* was the ruling class of civil servants, military officers and aristocrats during the Joseon Dynasty.

[5] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong [Independent activism of Korean Americans], (Hallim Taehakkyo Asia munhwa yŏn'guso, 1989) 334; Suzy Kim, Everyday Life in the North Korean Revolution, 1945-1950, (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2016) 144.

[6] Suzy Kim, Everyday Life in the North Korean Revolution, 144.

[7] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 332

[8] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 332-333

[9] The March 1st Movement of 1919 was a nation-wide protest calling for the end of Japanese Occupation of Korea that began in 1910.

[10] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 333

[11] The American Revolutionary Writers League was an organization of cultural producers and literary writers supported by the American Communist Party that became the more well-known League of American Writers in 1935.

[12] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 341.

[13] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 334, 341.

[14] Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 334.

[15] Suzy Kim, Everyday Life in the North Korean Revolution 141; Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 342.

[16] Suzy Kim, Everyday Life in the North Korean Revolution 141; Pang Sŏnju, Chaemihaninŭi Tongnip undong, 342.

[17] Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), 234.

[18] Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother, 234.

[19] Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother, 233.

[20] Stuart Hall, “Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities,” in Essential Essays Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora (Stuart Hall: Selected Writings), ed. David Morley (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019) 60.

[21] Stuart Hall, “Old and New Identities,” 78.

[22] Donna Lee Kwon has written about how pungmul in the U.S. cannot simply be understood as a “return to roots,” but Korean Americans have created an alternative entity fashioned from their diasporic transit and a complex network of transnational “routes.” See Donna Lee Kwon, “The Roots and Routes of Pungmul in the United States,” (2001). https://uspungmul.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/kwon2001.pdf.

[23] Lisa Kwon, “Korean Americans for Black Lives- KTown Organizes and Educates Against Anti-Blackness,” L.A. Taco, https://www.lataco.com/ktown-koreans-for-black-lives/.

[24] Simeon Man, “Anti-Asian Violence and US Imperialism,” Race and Class, Vol 62, issue 2, August 27, 2020, pp. 24-33.

[25] Antipode Online, Kenton Card. (2020). Geographies of Racial Capitalism with Ruth Wilson Gilmore [Video]. Antipode Foundation. https://antipodeonline.org/geographies-of-racial-capitalism/